A seminal report on prisons in Australia says that, across the nation and in other developed countries, governments contending with rising imprisonment and high levels of recidivism are on exactly the wrong path.

The current approach will only result in more prisoners, massive jail building programs, huge extra hits to taxpayers’ pockets…and more savvy ex-prisoners better ‘trained’ in committing crimes in the states’ detention centres.

By contrast, the report outlines a program for cutting the number of prisoners by up to 30%, rationalising the justice and legal system, and saving huge public expenditure over coming decades.

The Queensland Productivity Commission undertook a year-long study and extensive stakeholder and community consultation on a commission from the state government. Its recommendations provide a blueprint for how all states and territories must change how they approach the management and operation of prisons, Civil Liberties Australia believes.

Indeed, the QPC report strongly recommends major changes to legal and justice systems, as well as to the fabric of social structures which produce so many “prison-ready” potential criminals, then abandons them to a life of crime, criminal education inside prison, short release-and-return to prison for what, for some, has become a safe haven from the harsh reality of a world where they can’t cope.

As more people go to prison, community safety will decline, the QPC warns. It calls for a total overhaul of the entire criminal justice system.

Knee-jerk drug proposal reaction is negative

The cornerstone of the reform needed is decriminalising minor drug use. But the Queensland government’s knee-jerk reaction to the report instantly ruled out that option. Weak politicians and a rabid media are exacerbating the problem, and allocating public money wrongly, based on false premises, CLA says. “Public anxiety about crime is what drives state government investment in law enforcement,” as the QPC more diplomatically puts it.

“The law-n-order problem in society is a furphy,” CLA CEO Bill Rowlings said. “It is the make believe of shock jocks and news headline writers. The QPC report points out that murders and crimes against the person and against property are all hugely down over the past 20 years.

“But politicians cave in to demands – generated by the media and police unions – for more police, who arrest more people, who end up in jails, so new jails have to be built. The QPC report provides an opportunity to cut the Gordian knot.”

In a bitterly disappointing response, the Queensland government has given half-hearted support to change, and ruled out major corrections to justice and drug policy, CLA notes.

“… given the cost of keeping prisoners in prison, we need to examine whether that is the best option for people who repeatedly fail to pay fines, or are repeatedly arrested with small amounts of drugs for personal use,” Deputy Premier Jackie Trad said. “That’s especially true if that prison sentence pushes a small-time offender towards a life of more

crime, rather than rehabilitation.”

However, Deputy Premier Trad noted that the foreword to the QPC report acknowledged some of its proposed reforms would require wider community agreement and “should not be rushed”, but hoped the analysis would be the catalyst for further community debate.

“I’m afraid that ‘should not be rushed’ is pollyspeak for putting the QPC’s sensible recommendations in the too-hard basket,” CLA CEO Bill Rowlings said. “I note that Deputy Premier Trad has immediately ruled out drug law reform, but such reform is vital to achieve the changes needed.’

“If prison figures are anything to go by, some 40% of police work in Queensland is chasing people with health and mental health problems for whom minor drug use is a by-product of seeking escape from oppressed lives.”

‘ Politicians react to stirred-up public anxiety;

politicians drive up prison costs to taxpayers;

taxpayers fork out for pollies to enjoy power .’

*** The QPC report and government response are available here

Key points the QPC’s report makes:

In Queensland, imprisonment has been rising significantly faster than population growth—over the period 2012 to 2018 the number of people in prisons rose by around 58%, while population only grew by 9.7% (ABS 2019a).

The rate of imprisonment—the number of prisoners per head of population—has increased by more than 160% since 1992.

- This increase has primarily been driven by policy and system changes and a focus on short-term risk, not crime rates.

- The median prison term is short (3.9 months) and most sentences (62%) are for non-violent offences—30% of prisoners are chronic but relatively low harm offenders.

- Each month, more than 1000 prisoners are released back into the community. Over 50% will reoffend and return to prison or to a community correction order within two years.

- Social and economic disadvantage is strongly associated with imprisonment. Around 50% of prisoners had a prior hospitalisation for a mental health issue and/or were subject to a child protection order—for female Indigenous prisoners, this figure climbs to 75%.

On average, it costs $111,000 to keep an adult in prison for a year (and a further $48,000 in indirect costs for each person each year). In 2017–18, the total cost of running Queensland’s prisons was $960 million.

These costs are increasing. From 2011–12 to 2017– 18, real net operating expenditures on prisons increased by around 29%, significantly more than the increase in general government expenditures.

Queensland prisons are overcrowded — across all prisons, capacity is currently at 130% (the extra 30% is about 2000 prisoners). Without efforts to reduce demand, a significant expansion of capacity will be required. The Queensland Government has announced new cell capacity of nearly 1400 prison cells by 2023, at a total cost of $861 million.

The QPC report says that the current prison path is on a downward spiral. It says:

Costs to outweigh benefits

- The costs of imprisonment are likely to outweigh the benefits, with increasing imprisonment working to reduce community safety over time:

- While it costs around $111,000 per year to accommodate a prisoner, there are added, indirect costs in the order of $48,000 each person, each year.

- Prisons are not effective at rehabilitation, and can increase the likelihood of reoffending.

- Without action to reduce growth, the government will need to build up to 4200 additional cells by 2025. This will require investments of around $3.6 billion.

- Given the scale of policy reforms required, an essential first step will be to overhaul the decision-making architecture of the criminal justice system, including establishing an independent Justice Reform Office to provide a focus on longer-term outcomes and drive evidence-based policy-making.

- Many offending behaviours can be addressed outside of the criminal justice system through a victim restitution and restoration system, targeted community-level interventions and greater use of diversionary approaches.

- A lack of sentencing options constrains the ability to effectively deal with offending behaviours and makes the system costlier than it needs to be. More sentencing options are required including:

- more flexible community corrections orders supported by effective supervision and treatment, and

- supervised residential options that allow treatment to address offending behaviours.

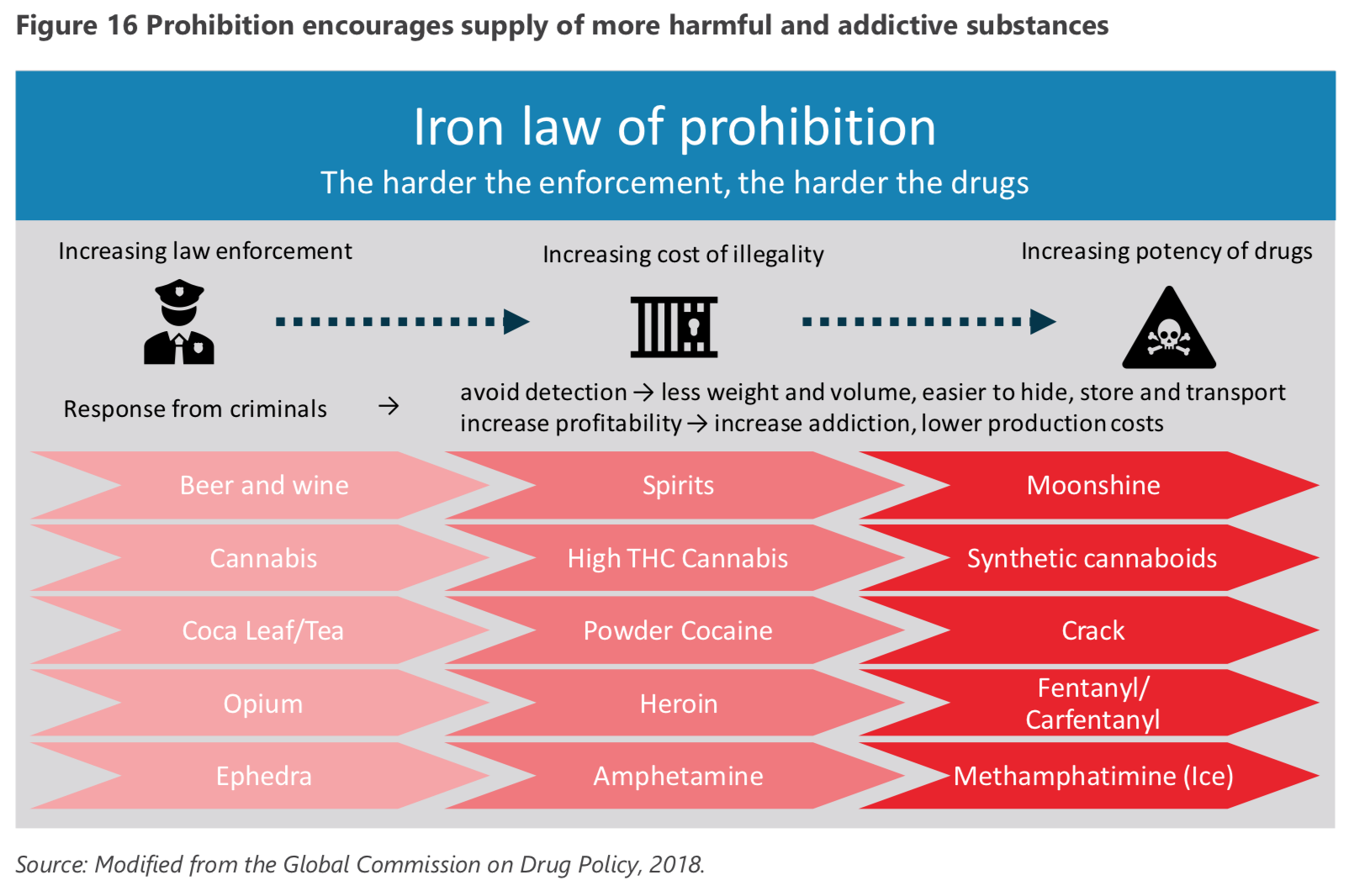

- After many decades of operation, illicit drugs policy has failed to curb supply or use. The policy costs around $500 million per year to administer and is a key contributor to rising imprisonment rates (32% since 2012). It also results in significant unintended harms, by incentivising the introduction of more harmful drugs and supporting a large criminal market.

‘Statistics show that the rate of drug-related accidental deaths has increased (by 144% since 1997), with illicit drugs now responsible

for more deaths than road accidents in Queensland.’

- Evidence suggests moving away from a criminal approach will reduce harm and is unlikely to increase drug use.

- High Indigenous incarceration rates undermine efforts to solve disadvantage—currently an Indigenous male in Queensland has an almost 30% chance of being imprisoned by the age of 25.

- Long- term structural and economic reforms that devolve responsibility and accountability to Indigenous communities are required. Independent oversight of reforms is essential.

- These reforms, if adopted, could reduce the prison population by up to 30% and save around $300 million per year in prison costs, without compromising community safety.

Prisons are a huge, and increasing, drain on taxpayer funds

The QPC report points out that the prison system is a huge drain on the state’s justice system, comprising – and costing – more than 25% of the total.

Inevitably, CLA points out, as a mushrooming prison system demands more and more expenditure in future, funds available to the other aspects of the justice system will decline relatively.

“It will be a case of the Queensland government robbing Peter to pay prisoners…and keep them in a system which doesn’t rehabilitate them, but churns them around through lives clouded by ill health and mental problems while being jobless and a problem to their families and the community,” Rowlings said.

“This is no small matter for taxpayers: Queenslanders are paying through the nose for their government to run a system that everyone admits doesn’t work, is over-expensive, in many ways inhumane…and is getting worse.

“On average, each Queensland taxpayer is paying about the equivalent, some $250, for a prisoner to stay in a luxury hotel for a day. In a few years, the taxpayer will be paying for the prisoner to stay two or three days in that ‘luxury hotel’.”

We are locking up Indigenous people faster than ever

The QPC report says that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are overrepresented in Queensland prisons. They comprise 4.6% of the state population, but 31.1% of the prison population. The age standardised rate of imprisonment for Indigenous Queenslanders is 10 times higher than for non-Indigenous people.

Between 2008 and 2018, the age standardised imprisonment rate for Indigenous people increased by around 45%, significantly faster (about 50% faster) than for the non-Indigenous rate (around 31%). For the whole of Australia, the increase in imprisonment rates was similar (45% versus 29%, respectively).

The Australian imprisonment rate (227.2 per 100,000 adults) is approximately the same as Queensland’s (221.4) (ABS 2018k). All Australian states and territories have experienced a growth in imprisonment rates. The Australian imprisonment rate also grew by 32% since 2012—a slightly slower growth rate than Queensland’s.

Amongst OECD countries, the United States’ incarceration rate is the highest, at 698 incarcerated people per 100,000 population, while Iceland’s rate is low, at 45 (2016 rates) (OECD 2016). Australia’s incarceration rate is listed as 152, slightly higher than the OECD and world averages, 147 and 144 respectively (OECD 2016; World Prison Brief 2016).

The QPC report says that a range of factors drive increases in the number of prisoners:

- increased reporting of crime;

- more use of prison sentences that other options;

- increasing recidivism;

- more effort by the police to clear up crime;

- increasing propensity for police to use court action rather than cautions, conferences, penalty notices and the like; and

- a significant increase in the proportion of prisoners on remand, especially over the past five years.

Longer or shorter sentences have little impact on imprisonment rates, QPC notes.

In 2017–18, the total cost of running Queensland’s prisons was $960 million. These costs are increasing. From 2011–12 to 2017– 18, real net operating expenditures on prisons increased by around 29%, significantly more than the increase in general government expenditures.

In the absence of any investments or policy change, the QPC projects the high security prison population will exceed design capacity by between 3000 and 4200 prisoners by 2025. To keep prisons within their original design capacity will require investments of between $1.9 billion and $2.7 billion beyond the $861 million already announced.

More imprisonment doesn’t benefit the community

Increasing policing effort has a much greater impact on crime than increasing the severity of punishment. Increases in sentence length do little to prevent crime, the QPC report says. Well-designed community corrections can reduce recidivism without compromising community safety.

In the first year in prison, inmates learn more about being a better criminal, CLA notes. Beyond that time, rehabilitation starts to kick in. But, CLA notes, most prisoners are in jail for less than four months, on average, which means that most prisoners learn more about committing crimes than not committing crimes while they are in jail, under the current system.

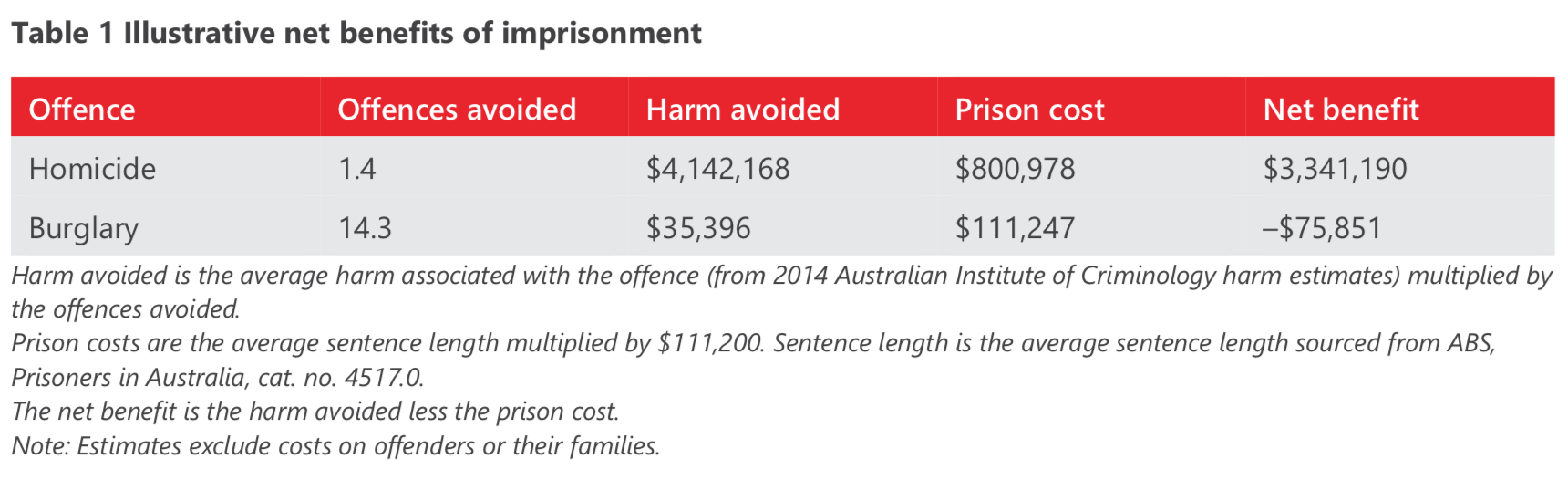

The QPC says that increasing the use of prison, particularly for less serious offences, is likely to impose a net cost on the community.

The Queensland system

There are over 11,000 sworn police officers, 200,000 criminal lodgements dealt with by the courts each year and 9000 prisoners managed in custody (11 high security prisons, 6 low security prisons, and 13 work camps). In 2017–18, the budgetary cost of the criminal justice system in Queensland (police, the courts and corrections) was around $3.5 billion.

Many other stakeholders play a role in the system—from oversight or advisory bodies like the Crime and Corruption Commission and the Queensland Sentencing Advisory Council, to legal services, service providers, representative groups and the media.

Murders, property and crime-against-the person: all massively down

The homicide rate in Australia is down from about 1.75 to 0.75 per 100,000 population over the past two decades. In Queensland over a similar period, crime against both property and against the person is down to about half what is was and two-thirds what is was 20 years ago.

Most Australians believe that crime rates have increased over the last few years, and about a third believe that crime has increased a lot. This is similar in other countries, where people commonly believe crime rates are rising, when in fact the opposite is occurring.

Similarly, the community often feel the judiciary is ‘out of touch’ or that sentences are too lenient and inconsistent. However, research shows that when given the full facts about a case, members of the public typically choose sentences that are on par with, or more lenient than, the imposed sentenced.

Public anxiety about crime is what drives state government investment in law enforcement. It is this investment, not underlying trends in crime, which has played the dominant role in shaping demand for criminal justice resources.

Most prison sentences are short. The median prison sentence in Qld is only 3.9 months. Often the whole sentence, or most of it, is served on remand — where opportunities for rehabilitation are limited. Non-violent offenders accounted for over 60% of all prisoners in 2017-18.

The QPC inquiry

QPC met with more than 600 stakeholders, received 89 written submission, held 150 meetings, visited eight jails, a number of courts and accommodation centres, and held direct consulted with Indigenous people in Hope Vale, Aurukun, Napranum and Yarrabah.

The rate of imprisonment in Queensland is currently higher than at any time since 1900. The prison population grew rapidly during two periods. From 1992 to 1999, the rate of imprisonment roughly doubled. It increased rapidly again from 2012 to 2018—growing by 44%.

Similar trends are occurring in the rest of Australia, CLA notes. All Australians jurisdictions should note this Queensland report, and take positive action as a result. Otherwise, prisons will send out states and territories broke, to the extent that prisoners will be receiving better treatment than the poor, the sick, the main, the mentally ill and anyone living life hard, on the edge.