The NSW Council for Civil Liberties helped to break the back of archaic Australian censorship laws by taking the fight to Sydney’s streets, which were then rife with police corruption. The Liberating of Lady Chatterley and Other True Stories is the tale of NSWCCL’s 44 years

The NSW Council for Civil Liberties helped to break the back of archaic Australian censorship laws by taking the fight to Sydney’s streets, which were then rife with police corruption. The Liberating of Lady Chatterley and Other True Stories is the tale of NSWCCL’s 44 years

Read this review by CLA President, Dr Kristine Klugman, who was there at the beginning. To buy a copy of the book ($24.95 plus p&p), contact CLA

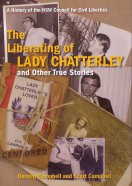

The Liberating of Lady Chatterley and Other True Stories

A History of the NSW Council for Civil Liberties

(by Dorothy and Scott Campbell, publisher: NSW Council for Civil Liberties 2007)

The forty-four year history of the NSW CCL is a tumultuous one: it could be observed that getting (mostly) lawyers to agree and act in concert is very like herding cats.

This is a timely and well-written history of the activities of a group of committed people acting to defend freedoms. As an early participant, one is reminded of half-forgotten campaigns and issues, people and circumstances, excitement and frustration: events certainly worth recording. I am very glad the authors took the extensive trouble they did.

.

The founders were an improbable trio: leftie academic historian, right-wing medico and witty lawyer. Ken Buckley, Dick Klugman and Jack Sweeney were friends who shared a philosophy of anti-authoritarianism and pro people’s rights vis-a-vis the state. Almost inevitably, there is underlying antipathy between civil libertarians and police as custodians of the law.

The NSW CCL was very much a product of its time – with rampant police corruption and brutality so incensing Buckley that he rang and met with his mates, contacted a group of like-minded people and held a public meeting. He went on to make the NSWCCL his life’s work. Through the pages of this history, his tenacity and single-minded, even stubborn, drive to pursue the basic rights of people to live their lives free of interference from authorities becomes apparent. I believe that without him, the NSWCCL would not have survived and become influential.

The original aims of the CCL were to oppose:

- censorship of books, films and TV;

- restrictions on free speech;

- police excesses;

- inequality in migration policy;

- discrimination against Aborigines; and to

- strive for constitutional guarantees.

With a basic belief in the vital importance of civil liberties and a stubborn refusal to be defeated, the NSWCCL has had a significant impact on the political and social life of the community. The chapter headings and length indicate the CCL’s historical focus, with primary attention given to police, immigration, censorship and prisons and less space to women’s rights and a bill of rights.

There are some good stories recounted of battles won and lost. I leave those for the reader to discover. The lesson which shines through is that, though civil liberties issues are often sensational and newsworthy, the hard yards are won in time-consuming writing of submissions, making representations, meetings, consultations, education campaigns, writing articles and books and policy debates.

One of the most significant early initiatives was the publication in 1964 of a booklet – If You Are Arrested, which was republished in 1987 and 1993. It outlined in simple terms the rights of people arrested and made the name of the NSWCCL.

The triumph of the Lady Chatterley anti-censorship campaign from 1964 was carried on the assertion that adults should be free to read and view what they choose. The activist campaigners used satire to shock – and were usually arrested.

Aboriginal rights were an early concern for the NSWCCL, before such campaigning became fashionable. The Brindle case, according to Buckley, “was the CCL’s first real victory” (p50), and demonstrated that Aboriginal people could win just cases in court, with a little help from their friends. The Aboriginal Deaths in Custody Royal Commission of 1987 was strongly supported by the CCL, whose members stressed that not only the direct causes but also the underlying social and economic conditions of problems should be investigated.

There are significant events recounted which are milestones in social history of NSW: the disturbing record of the Bathurst riots and how the CCL pressed for a Royal Commission into prisons, the work in migrants’ rights, against censorship and pressing for the rights of people to read and see what they choose, the rights of women to decide what happened to their bodies…

The CCL has striven to avoid party political-connection. Though even the most radical members have attempted to keep civil liberties and politics separated, the CCL has been labelled a left-wing ratbag organization by conservative forces. Against this, there was the famous incident in 1984 when foundation member, Labor Premier Neville Wran, berated the Council for failure to support one-time federal Attorney-General and High Court Justice, Lionel Murphy (p19) – another story worth reading.

Most frequently, the CCL found itself being critical of conservative governments, but it did not hesitate to attack any laws or authorities it felt was infringing on rights. There was a tacit understanding that political issues which had the potential of dividing the Council should be avoided.

The nature of society has changed since the formation of the NSW CCL. In 1963, there were no groups to assist disadvantaged minorities: no Legal Aid, no Aboriginal Legal Service, Migrant Legal Service, Women’s Legal Service, Ombudsmen, Gay Rights groups, Prisoners’ Associations. Many of the early Council members did pro bono work, representing such people. And, as High Court Justice Michael Kirby points out in the Foreword, many went on to important legal positions.

The challenge for today’s civil liberties groups is to anticipate issues which will have an huge impact in a decade or two from now: issues like CCTV surveillance, protection of personal data, who holds and secures our DNA, ID cards, the impacts on rights of rising sea levels and environmental refugees, freedom of information in the electronic age, electronic prisons, the draconian anti terror laws and of course a national bill of rights.

We who are engaged in working for civil liberties could not aspire to anything more than the aim expressed by Ken Buckley: “…we will keep up the struggle for justice and freedom for all” (p183).

Review by: Dr Kristine Klugman OAM, President, Civil Liberties Australia, December 2007

To buy the book ($24.95 plus p&p), contact CLA via our contact form