If Australians fear unionist power, why would that be so? Or is there in fact a rising tide of even more deep-seated suspicion of employers, just waiting for one or other party to curtail with curbs on bosses and their salaries? This telling Norman Abjorensen article explains the background, and what surveys reveal.

If Australians fear unionist power, why would that be so? Or is there in fact a rising tide of even more deep-seated suspicion of employers, just waiting for one or other party to curtail with curbs on bosses and their salaries? This telling Norman Abjorensen article explains the background, and what surveys reveal.

Unions: a crucial part of healthy democracy

Norman Abjorenson

This article first appeared in The Canberra Times of 24 Oct 07.

It was famously once said of Benito Mussolini’s dictatorial rule in Italy that whatever faults he had, he at least made the trains run on time.

It is a remark at once humorous and incisively serious, drawing attention to democracy and its defects, and what the alternatives might be in addressing those defects.

Democracy is, of course, notoriously inefficient. Paradoxically, its very strength lies in that inefficiency by diffusing centres of powers and institutionalising a self-regulatory mechanism of sometimes cumbersome checks and balances.

We have that aplenty in Australia, the federation and the sometimes complex divisions of power and responsibilities between the Commonwealth and the states and territories being just the best known example. The independent judiciary is another, as is the bicameral Parliament, dividing legislative responsibility between the Senate and the House of Representatives.

It is messy, it is awkward, it is sometimes both bewildering and confusing. And above all it is inefficient in the extreme. But it is necessary: it is how we guard against tyranny. In other words, what are we prepared to surrender to have the trains run on time? Are punctual trains worth the elimination of liberty? What price are we prepared to pay as in late trains and other irritations to safeguard our political and personal freedoms?

Our rights and liberties, as practised in a democracy, are taken for granted. The distinguished philosopher, A.C.Grayling, in his just published meditation on the long struggle for freedoms, Toward the Light of Liberty, makes the eloquent point that "today’s ordinary Western citizen is, in 16th-century terms, a lord: a possessor of rights, entitlements, opportunities and resources that only an aristocrat of that earlier period could hope for."

To Grayling, this is the direct result of a singular process in the form of enfranchisement, consisting in the increasing liberty of the individual, the growth of the idea that individuals have rights and claims, and that they can assert themselves against the constituted authority of the land.

Democracy in the 20th century faced dire challenges from the left and the right in the form of fascism and communism. But the current crisis is more pervasive and gradual: erosion from within.

Since the 1970s, there has been a movement against democracy, mostly triggered by an international organisation called the Trilateral Commission, a body founded by banker David Rockefeller to co-ordinate and protect capitalism in the United States, Europe and Japan. In 1975 it commissioned a report, The Crisis of Democracy, in which the thesis was advanced that the West was slowly becoming ungovernable owing to too much democracy, and its economic prosperity depended on winding it back.

It was no coincidence that US president Ronald Reagan and British prime minister Margaret Thatcher attacked trade unions and drastically curtailed their rights. Australian Prime Minister John Howard’s current campaign is merely an ideological continuation of that.

Unions play a crucial role in a democracy. They are all that stand between rapacious employers and otherwise powerless workers.

It is worth reflecting that by far the greater part of our lives is spent in the workplace where democracy is all but unknown. The union is the necessary check and balance to the generally undemocratic and total power wielded by an employer in the workplace, where the employee has no democratic rights.

Unions never ran the country, as the Prime Minister is so fond of repeating, but at least they offered a modicum of protection in the workplace that the current Government is so intent on curtailing or even eliminating. The effect of the policy is a wholesale disenfranchisement of the workforce. The justification for this assault is the same argument as getting the trains running on time. Is it a price we are prepared to pay?

The evidence suggests the Prime Minister seeks to articulate a message that is not shared by the electorate, despite declining union membership. Whose interests might be seen to be served by this? Is it consistent with democratic practice?

The respected Australian Election Study has measured attitudes for years. Asked whether trade unions had too much power, 35.4per cent of those surveyed answered yes (strongly agree) in 1990, 38per cent in 1993, 37.6per cent in 1996, 24.2per cent in 1998, 19.4per cent in 2001 and 15.5per cent in 2004.

On the other hand, asked whether big business had too much power, 22.1per cent strongly agreed in 1990, 27.7per cent in 1993, 29per cent in 1996, 31.1per cent in 1998, 31.8per cent in 2001 and 27.1per cent in 2004. So much for the so-called spectre of trade unions. The public, clearly, have other fears.

Dr Norman Abjorensen teaches politics at the ANU. He is a Visiting School Fellow, Political Science & International Relations, in the School of Social Sciences.

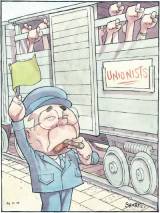

Cartoon caption: Is this what’s meant by ongoing training for workers? Canberra Times cartoonist and CLA member Ian Sharpe’s comment on the Abjorensen article.