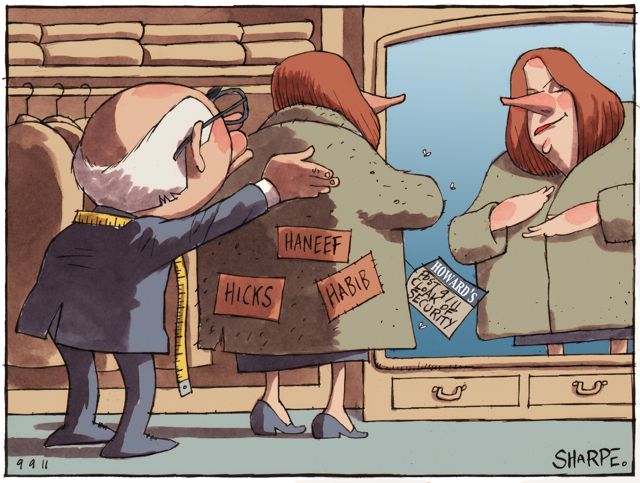

Australia’s counter-terrorism law and policy is ‘close to moral and political bankruptcy’, Dr Chris Michaelsen writes. He calls for a comprehensive review and reform of Australian anti-terrorism laws – ‘the most draconian in the Western world’ – as well as an inquiry what went wrong in the cases of Habib and Hicks.

Australia’s counter-terrorism law and policy is ‘close to moral and political bankruptcy’, Dr Chris Michaelsen writes. He calls for a comprehensive review and reform of Australian anti-terrorism laws – ‘the most draconian in the Western world’ – as well as an inquiry what went wrong in the cases of Habib and Hicks.

‘Gigantic’ policy at odds with reality of risk

By Dr Chris Michaelsen*

Ten years ago the terrorist attacks in the Unites States shook much of the world to its core. At first, the catastrophic events seemed a world away for many Australians, who felt confident that geographical fortuity insulated them from international turmoil.

However, this perception changed ultimately 13 months later when terrorists bombed two night clubs in Bali. Among the 202 people killed on 12 October 2002 were 88 Australian tourists.

The Bali bombings were commonly seen as evidence that terrorism had arrived on Australia’s doorstep. Indeed, this proposition was actively advanced by the Howard government which cited the Bali bombings as evidence that international terrorism had reached Australia. In the years to come terrorism was portrayed as the supreme threat to Australia and the Prime Minister and other senior cabinet ministers repeatedly sought to capitalise on the issue politically, often employing the most colourful language.

Launching the government’s White Paper in 2004, for instance, the then Foreign Minister, Alexander Downer, boldly proclaimed that Australia was engaged in a ‘struggle to the death over values’ against ‘Islamo-fascists’ who were ‘convinced that their destiny was to overshadow the democratic West’ and who had embarked on a ruthless mission to ‘destroy our society by waging a version of total war’.

The government’s response, however, was not limited to martial rhetoric. Since 2001, Australia’s total defence spending has increased 59% from $13.7 billion to $21.8 billion. Over the same period, ASIO’s budget has increased by 655%, the Australian Federal Police budget by 161%, ASIS by 236% and the Office of National Assessments by 441%. (While ‘security’ received a massive boost, diplomacy suffered: in the same broad timeframe, 1996 to 2008, Australian Public Service staffing numbers overall grew 25 to 30%, but the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade actually contracted by 11%).

The legislative response has been unprecedented, too. Since 9/11, federal parliament has enacted more than 40 pieces of ‘security legislation’ which ensure that Australia has some of the most draconian anti-terrorism laws in the Western world. In fact, Australia is the only Western liberal democracy that allows its domestic intelligence agency, ASIO, to detain persons for seven days without charge or trial and without reasonable suspicion that those detained are actually involved in any terrorist activity.

This gigantic policy response has been at odds with the reality of the risk of terrorism in Australia. To date, not a single person has been killed in a terrorist attack on Australian soil in the post-9/11 era. Around 100 Australians have died in terrorist attacks overseas, most of them in the Bali bombings.

Indeed, chances of dying in a terrorist attack in Australia are close to zero. A calculation of annual fatality risks for the period of 1970-2007 reveals that the risk of getting killed in a terrorist attack in Australia is 1 in 33,300,000. Even with the Bali bombings included, the fatality risk stands at 1 in 7,100,000. By comparison, the risk of a fatal traffic accident amounts to 1 in 15,000.

Figures at the legal front tell a similar story. In spite of the prolific legislative activity in the field of counter-terrorism over the past decade, few criminal prosecutions and even fewer convictions have resulted from the legislative changes.

Of the 37 people charged under new anti-terrorism laws, not one was charged for actually engaging in a terrorist act. Instead, the 25 defendants who ended up getting convicted were prosecuted under extremely broad ancillary offences such as ‘collecting documents connected with the preparation for a terrorist act’. The low number of convictions – one-in-three people charged were found by the courts to be innocent – illustrates that Australia is not host to cohorts of ruthless terrorists, even if there is some evidence to suggest that a small number of individuals have trained with militant organisations overseas.

At the same time, the increase of investigatory, control and detention powers of Australia’s security agencies has not resulted in large-scale violations of civil liberties. Despite the mishandled affair of Gold Coast doctor Mohammed Haneef and the unlawful kidnapping of Sydney student Izhar ul-Haque by ASIO, Australia has not turned into an Orwellian police state.

Nonetheless, the government’s counter-terrorism law and policy has had harmful effects on Australia’s Muslim communities. Although the laws are expressed in ethnically and religious neutral terms, there is a perception amongst Australian Arabs and Muslims that they are targeted by these laws and by those who apply them. This has led to the alienation of some members of those communities, increased fear and insecurity and created a growing distrust of authority.

A further negative effect of Australia’s counter-terrorism law and policy has been that extraordinary legislative measures are normalised and adopted to address other areas considered to be risks to public safety. Recent non-terrorism laws in South Australia and New South Wales have adopted provisions and arrangements similar to those of federal anti-terrorism legislation but aimed at criminal organisations and bikie-gang violence. The High Court of Australia has subsequently struck down these laws. Yet, the temptation for legislators to use federal anti-terrorism legislation as a blue print for developing laws aimed at responding to the nuisances of the day remains.

In spite of obvious shortcomings of Australia’s counter-terrorism law and policy, the Labor governments of Kevin Rudd and Julia Gillard have so far shown little enthusiasm for comprehensive review and reform. In 2010, the government adopted the National Security Legislation Amendment Act 2010 (Cth). While comprehensive in size, this legislation did little to address the worst aspects of Australia’s flawed anti-terrorism laws. At the time these reform efforts were rightly described by some experts as doing little more than tinkering around the edges of existing legislation.

Similarly, it took the government 10 years to establish and appoint Australia’s first Independent National Security Legislation Monitor. This position, currently held in a part-time capacity by Sydney silk Bret Walker SC, is mandated to review the operation of anti-terrorism legislation. While certainly a welcome improvement of current oversight arrangements, it remains to be seen how much Mr Walker can actually achieve: his office is operating with an annual budget less than the cost of three special counter-terrorism vehicles recently received by the police in South Australia, the Northern Territory and the ACT.

The most shameful episode in Australia’s ‘war on terrorism’, however, has been the treatment of former Guantanamo detainees Mamdouh Habib and David Hicks. In the case of Habib, both Coalition and Labor governments have consistently denied any knowledge of his presence in Egypt between his arrest in Pakistan and his transfer to Cuba. These denials must now be seriously questioned. Leaked witness statements suggest that Australian officials not only knew of Habib’s rendition but were also present when he was tortured in Egypt.

The abandonment of an Australian citizen by his government and its complicity in torture raises serious questions. Nevertheless, rather than setting up a public inquiry into the matter, the Gillard government, in December 2010, paid an undisclosed amount of money to Habib in return for his dropping a civil case against the government and signing a confidentiality agreement.

The latest developments in the Hicks case are equally disquieting. Documents from the office of the former US vice-president, Dick Cheney, suggest that John Howard called in a political favour from the US government amidst his ill-fated bid for re-election in 2007. Howard desperately begged the Americans to get any charge possible laid against Hicks whom he had earlier branded as among the ‘worst of the worst’ terrorists at Guantanamo.

These disclosures also shed an interesting light on former Howard ministers like Philip Ruddock who recently resurfaced from political oblivion to voice his support for the confiscation of royalties which Hicks received from the publication of his autobiographical book ‘My Journey’. Leaving the technical legal flaws of the pending court case aside, the matter is a classic case of applying double standards: if the notorious Chopper Read and white collar criminals are allowed to profit from their memoirs, then so should Hicks, in particular in light of the fact that his ‘conviction’ was handed down by a military tribunal which was severely compromised in all sort of respects.

Commentators in the United States have described the past 10 years as the country’s ‘lost decade’. The disproportionate focus on terrorism is seen as having played its part in Washington’s road to economic disaster.

Australia has escaped similar financial calamities. Yet, its counter-terrorism law and policy is close to moral and political bankruptcy. The 10th anniversary of the 9/11 attacks provides an opportune moment to correct that course. A comprehensive review and reform of anti-terrorism legislation as well as a public inquiry into what went wrong in the cases of Habib and Hicks would be a good way to start. Such an exercise may be painful and embarrassing. And it may require political courage.

But if Britain and Canada can do it, why not us?

ENDS

Dr Chris Michaelsen is a Senior Research Fellow at the Faculty of Law, University of NSW, and the author of ‘Security, Politics and Law in Australia’s War on Terror’, to be published by ANU E Press late in 2011. He is a member of CLA.

A slightly shorter version of this article appeared first in the Canberra Times:

http://www.canberratimes.com.au/news/opinion/editorial/general/our-flawed-responses-to-911/2286542.aspx?storypage=0