High Court rules against refugees

Refugees on Nauru and Manus islands had pinned their hopes on beating the Commonwealth of Australia seven-judge team on the field of the High Court: but they lost 6-1. Umberto Torresi explains how the Australian Government committed a number of near-fouls, and should probably have been given a red card. PS: The ‘umpiring panel’made a bad call, he says.

By Umberto Torresi

On 3 February 2016 the High Court of Australia handed down its decision in the case of PlaintiffM68/2015 v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection and Ors [2016] HCA 1. A majority of the Court [French CJ, Kiefel and Nettle JJ and in separate judgments Bell J, Gageler J and Keane J] found for the defendants, that is, for the government. In her dissenting judgment, her Honour Justice Gordon found for the plaintiff.

The following is a necessarily greatly curtailed summary of a 118-page judgment necessarily presenting only the main points of their Honours’ reasoning. For example, arguments about the plaintiff’s standing to bring the proceedings [which all judges accepted she had] and questions about the relevance of the Nauru constitution for the validity of the Australian laws in question are not discussed.

The plaintiff

Plaintiff M68 was a Bangladeshi national who, on entering Australia’s migration zone, was taken to Nauru pursuant to s198AD(2) of the Migration Act 1958, which provides for the removal of any ‘unauthorised maritime arrival’ to a ‘regional processing country’, of which Nauru is one.

The plaintiff did not consent to being taken to Nauru. She did not consent to being detained in Nauru’s detention centre.Upon her arrival on Nauru the plaintiff applied to be recognised as a refugee by Nauru.

She was granted a regional processing centre visa pursuant to the applicable Nauru regulations. She did not apply for that visa – the application could only be made and was made on her behalf by an Australian officer. The Commonwealth paid the visa fee.

By reason of being granted the visa, the plaintiff was a ‘protected person’ under the Nauruan Migration Act[1] and, as such, she could not leave the centre without the approval of an authorised officer. It was an offence on Nauru, punishable on conviction to imprisonment for a period not exceeding six months, for any protected person to leave or attempt to leave the centre without permission.

If she were to be recognised by Nauru as a refugee her visa would become a temporary settlement visa, she would no longer be required to reside at the centre and could depart and re-enter Nauru.

On 2 August 2014, officers of the Commonwealth brought the plaintiff to Australia for obstetric and gastroenterological review. She was approximately 20 weeks pregnant.

Media reports suggest the plaintiff had health issues to do with her pregnancy. She has since given birth in Australia to a girl who is now aged approximately 13 months.

The plaintiff no longer needed to be in Australia for her health issues, was liable to be returned to Nauru and applied for an injunction preventing her removal.

The plaintiff also sought a writ of prohibition prohibiting the respondents from taking steps to remove her to Nauru if she was to be detained at the centre and orders prohibiting and restraining the Commonwealth from making future payments to Transfield pursuant to its contract.

Her application to be recognised as a refugee in Nauru had not been determined by the time of the High Court’s decision.

The conditions in which the plaintiff was detained

Memoranda of understanding and administrative arrangements between the two countries governed the transfer to and presence in Nauru of asylum seekers like the plaintiff, including the arrangements by which they are physically detained there. Pursuant to the arrangements, Nauru agreed those concerned would stay lawfully in the country and Australia agreed to lodge visa applications on their behalf.

The centre in which the plaintiff was detained comprised three sites. One contained the administrative offices and also housed Australian Border Force Officers who performed various functions including supervising service providers, communications and construction projects. Another housed asylum seekers who were single adult males. A third [RPC3] housed single adult females and families. The Commonwealth contracted for the construction and maintenance of the centre, and funds all costs associated with it, in accordance with the arrangements.

From 24 March 2014 to 2 August 2014, the plaintiff resided in RPC3, surrounded by a high metal fence through which entry and exit was possible only through a permanently monitored checkpoint. The plaintiff was able to move freely within RPC3 save for certain restricted areas and at specified hours. However, if the plaintiff had attempted to leave the centre without permission, the centre staff would have sought the assistance of the Nauruan Police Force. An authorised officer, an operational manager of the centre or other authorised persons could give permission for her to leave the centre. The Secretary of the Department of Justice and Border Control of Nauru appointed Wilson Security staff as authorised officers. No Commonwealth officers were appointed as authorised officers.

A Nauruan appointed operational manager was in charge of the day-to-day management of the centre. An Australian appointed program coordinator was responsible for managing all Commonwealth officers and service contracts in relation to the centre, including the contracting of a service provider to provide services at the centre for transferees and to provide for their security and safety. A Joint Committee and a Joint Working Group were established.

The implementation of the regional partnership between Australia and Nauru was overseen by a Ministerial forum that provided updates on the delivery of projects in Nauru, including the operation of the centre. It was co‑chaired by the Commonwealth Minister and by the Nauru Minister for Justice and Border Control. The Joint Committee, comprising representatives of the respective governments, met regularly to discuss the operation of the centre. The Joint Working Group, chaired by the Nauru Minister, met each week to discuss matters relating to the centre, including regional processing issues.

Transfield[2] provided security, cleaning and catering services. As service provider it was required to ensure that the security of the perimeter of the site was maintained. The Department provided fencing, lighting towers and other security infrastructure.

The proceeding

In issue in the case was whether there was statutory and constitutional support for the Australian government’s involvement in the detention arrangements that restricted the plaintiff’s liberty.

In the course of the proceeding the Government of Nauru implemented arrangements by which operational managers could grant permission for those detained there to leave the centre at certain times, subject to conditions, and removed the restrictions on movements of visa holders.

Also in the course of the proceeding, the Commonwealth Parliament inserted s198AHA into the Migration Act to authorise the Commonwealth to take any action and make any payment in relation to the arrangements and regional processing functions of the country concerned [ie Nauru].

Any ‘action’ was defined in s 198HA(5) to include ‘exercising restraint over the liberty of a person’, and so including the use of physical force.

In summary the plaintiff argued that the Commonwealth and the Immigration Minster, by their conduct in connection with arrangements had constrained her liberty, including by her detention and by entering into contracts and the expenditure of monies in connection with those constraints, the Commonwealth had effective control over those constraints and the conduct was not authorised.

The Commonwealth argued that:

- Section 61 of the Constitution [executive power, execution and maintenance of the laws of the Commonwealth] authorised it to enter into the arrangements with Nauru.

- Section198AHA was statutory authority for steps taken to give effect to the arrangements.

and

- The plaintiff’s detention on Nauru was by the Government of Nauru.

French CJ, Kiefel and Nettle JJ

Their Honours considered that, given the steps Nauru had taken, to permit those detained there to leave the centre and move about the country without restriction, there was no longer a basis for the plaintiff’s case for an injunction and writ complaining of her detention at the centre.

Their Honours characterised the plaintiff’s case as being that the extent of the Commonwealth’s participation in her detention was not authorised by statute or otherwise.

The Commonwealth had the statutory power in s198AD(2) of the Migration Act to remove the plaintiff from Australia to Nauru and to detain her for that purpose. Section 198AD(2) is a law with respect to a class of aliens and so is a valid law within s 51(xix) of the Constitution. The legislative power conferred by s 51(xix) includes Executive (that is, Government) authority to detain an alien in custody for the purposes of deportation or expulsion. That power is limited by the purpose of the detention and exists only so long as is reasonably necessary to effect the removal of the alien. The Commonwealth’s power to detain the plaintiff for the purpose of removing her from Australia and taking her to Nauru ceased upon her being handed over into the custody of the Government of Nauru.

The plaintiff thereafter was detained in custody under the laws of Nauru, administered by the Executive government of Nauru. Even if the plaintiff was taken to Nauru without her consent, the Nauru Immigration Act applied to her.

The plaintiff was confined to and was not free to leave the detention centre because of the conditions of her Nauruan visa and the Nauru Act that made it an offence for her to leave it without permission.

Because the Secretary of the Department of Justice and Border Control of Nauru appointed Wilson Security staff as authorised officers and no Commonwealth officers were appointed as authorised officers, the restrictions applied to the plaintiff were the independent exercise of sovereign legislative and executive power by Nauru.

The Commonwealth could not compel or authorise Nauru to make or enforce the laws that required the plaintiff be detained. If Nauru had not detained the plaintiff, the Commonwealth could not itself do so.The Commonwealth did not itself detain the plaintiff.Therefore the plaintiff’s case actually concerned the participation by the Commonwealth and its officers in her detention by Nauru.

That participation in the detention of the plaintiff on Nauru must be authorised by the law of Australia. Section 198AHA of the Migration Act provided that authority.The section was a law with respect to aliens supported by the aliens power in s 51(xix) of the Constitution. It concerned the functions of the place to which an alien is removed for the purpose of their claim to refugee status being determined. The requirement that there be a connection between the subject matter of aliens and the law that is more than insubstantial, tenuous or distant is satisfied.

Bell J

Section 198AHA provides a complete answer to the plaintiff’s case. Nauru is designated as a regional processing country under s 198AB of the Migration Act. Section 198AHA applies because the MOU is an arrangement entered into by the Commonwealth in relation to the regional processing functions of Nauru. Section 198AHA(2) confers authority on the Commonwealth to make payments and to take, or cause to be taken, any action in relation to the arrangement or the regional processing functions of Nauru. Action includes exercising restraint over the liberty of a person in a regional processing country. The regional processing functions of a country include the implementation of any law or policy, or the taking of any action, by a country in connection with its role as a regional processing country.

The actions and payments in relation to the regional processing functions of the regional processing country authorised by s 198AHA(2) are, in legal operation and practical effect, closely connected to the processing of protection claims made by aliens who have been taken by the Commonwealth from Australia to the regional processing country for that processing. This provides a sufficient connection between s 198AHA and the power conferred by s 51(xix)

The Commonwealth funded the RPC and exercised effective control over the detention of the transferees through the contractual obligations it imposed on Transfield. Thus the plaintiff’s detention in Nauru was, as a matter of substance, caused and effectively controlled by the Commonwealth parties.

A law, authorising or requiring the detention in custody of an alien without judicial warrant, will not contravene Chapter III of the Constitution provided the detention that the law authorises or requires is limited to that which is reasonably capable of being seen as necessary for the purposes of deportation or for the purposes of enabling an application by the alien to enter and remain in Australia to be investigated and determined. So limited, the detention is an incident of Executive power. If not so limited, the detention is punitive in character and ceases to be lawful.

The requirement for transferees to be detained, while the administrative processes involved in the investigation, assessment and review of their claims take place, does not thereby take on the character of being punitive.

However, if a transferee were to be detained for a period exceeding that which can be seen to be reasonably necessary for the performance of those functions, the Commonwealth parties’ participation in the exercise of restraint over the transferee would cease to be lawful.

Gageler J

The Executive Government of the Commonwealthphysically detained the plaintiff in custody on Nauru, through its de-facto agent Wilson Security.That any physical restraint of the plaintiff would only have occurred as a result of calling in the Nauruan Police Force does not affect that conclusion.

The procurement of the plaintiff’s detention on Nauru by the Executive Government of the Commonwealth under the Transfield contract was beyond the executive power of the Commonwealth unless it was authorised by valid Commonwealth law. Before 30 June 2015, there was no applicable Commonwealth law. On that day, s 198AHA was inserted with retrospective effect to 18 August 2012.

In so far as it authorised the Executive Government to take action or cause action to be taken outside Australia in relation to an arrangement entered into by the Executive Government and the government of a foreign country, it is a law with respect to external affairs, within the scope of s 51(xxix) of the Constitution. In so far as it authorised the Executive Government to take action or cause action to be taken outside Australia that involves, or is incidental or conducive to, assessment in that country of claims to refugee status by non-citizens who have been transferred from Australia, it is also a law with respect to aliens, within the scope of s 51(xix) of the Constitution.

The duration of the resulting detention must be reasonably necessary to effectuate a purpose which is identified in the statute conferring the power to detain and which is capable of fulfilment. The duration of the detention must also be capable of objective determination by a court at any time and from time to time.

The extent to which action taken on the authority of s 198AHA(2)(a) may involve detention is, on that reading, limited to detention that is in connection with the role of the regional processing country as specified in the arrangement. The requisite connection with that role would be broken were the duration of the detention to extend beyond that reasonably necessary to effectuate that role or were that role to become incapable of fulfilment. The duration of the detention is in the meantime capable of objective determination by a court by reference to what remains to be done by the regional processing country to fulfil its role as specified in the arrangement.

Keane J

The plaintiff’s detention in Nauru was not detention in the custody of the Commonwealth. It was in the custody of the Republic of Nauru. That is because the legal authority by which she was held in custody in Nauru, an independent sovereign nation, was that of Nauru and not that of the Commonwealth.

To the extent that statutory authority was necessary to enable the Commonwealth lawfully to procure or fund or participate in the restraints over the plaintiff’s liberty which occurred in Nauru, that authority was provided by s 198AHA(2) of the Migration Act.

Section 198AHA seeks to ensure the reasonable practicability of removal to a country willing and able to receive these aliens. This operation is sufficient to enable s 198AHA to be characterised as a law with respect to aliens within s 51(xix) of the Constitution.

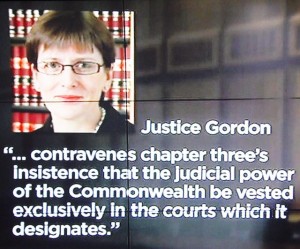

Gordon J (dissenting)

The Commonwealth took the plaintiff to a place outside Australia, namely Nauru.

On Nauru, the Commonwealth did not discharge the plaintiff from its detention. Despite having removed the plaintiff to a place outside Australia, the Commonwealth intended to and did exercise restraint over the plaintiff’s liberty on Nauru, if needs be by applying force to her. Notwithstanding that there was no explicit mention of detention in the relevant memoranda and administrative arrangements, the Commonwealth detained the plaintiff on Nauru by its acts and conduct.

The detention of the plaintiff by the Commonwealth on Nauru, which the Commonwealth asserts s 198AHA both requires and authorises, is not limited to what was reasonably capable of being seen as necessary for the purposes of removal of the plaintiff from Australia (or the prevention of the plaintiff’s entry into Australia). Removal from Australia was complete when the plaintiff arrived on Nauru. Moreover, the detention by the Commonwealth on Nauru was not necessarily to enable an application for an entry permit to Australia to be made and considered. The plaintiff is unable to make such an application. Further, the plaintiff’s detention by the Commonwealth on Nauru could not have been for the purpose of completing Australia’s obligation to consider her application for refugee status, because that obligation rested on Nauru.

The detention of the plaintiff (either at all or in its duration) was not reasonably necessary to effect a purpose identified in the Migration Act which was capable of fulfilment. The object of the Migration Act is to regulate, in the national interest, the coming into, and presence in, Australia of non-citizens. The plaintiff’s detention was not reasonably necessary for that stated object or any of the other stated purposes which are set out in s 4 of the Migration Act to “advance” that stated object.

The aliens power does not provide the power to detain after removal is completed.

It is the detention by the Commonwealth of the plaintiff outside Australia and after the Commonwealth exercised its undoubted power to expel her from Australia, or prevent entry by her into Australia, that cannot be lawfully justified.

The Executive Government of Australia cannot, by entering into an agreement with a foreign state, agree the Parliament of Australia into power. The removal of an alien to a foreign country cannot sensibly be said to continue once that alien has been removed to that foreign country. Upon the plaintiff’s arrival on Nauru, the Commonwealth’s process of removal was complete and the purpose for which removal was undertaken had been carried out. Removal was not ongoing. Australia can provide assistance to Nauru. But Australia cannot detain the plaintiff on Nauru.

Comments

When one considers the context of the plaintiff M68 case, it is reasonable to opine the majority judgments in the case are deeply unsatisfying and the dissenting judgment of her Honour Justice Gordon is to be preferred.

Plaintiff M68 was a lone Bangladeshi asylum seeker, who became pregnant while in detention against her will on Nauru, who later gave birth in Australia, whose status as a refugee remained undetermined at the time of the High Court’s judgment, and who faced being returned to Nauru with her child. She [and her child] would not be returned to detention there but would face an indefinite wait to know her fate as a refugee or otherwise. Pitted against her was and is the formidable power of the State, by which she had been detained under arrangements that persisted until after she brought her case to the attention of the Court, and which responded – with palpable cynicism – to negate her complaint by enacting s 198AHA of the Migration Act.

All of the Justices considered that the Commonwealth’s power to detain plaintiff, restrict her liberty and participate in arrangements with Nauru in respect of her, could not be without limitation.

But the majority’s prescription of that limitation, that it cannot extend beyond that reasonably necessary to effectuate the assessment of the plaintiff’s status in Nauru or were that role to become incapable of fulfilment, is an inadequate standard. That is because, to be able to invoke the standard, plaintiff M68 must return to the conditions she complains of as unlawful – not detention, but Australia’s participation in the arrangements by which her status is to be determined by Nauru – and wait for an indefinite time to either know here fate or be in a position to mount a further challenge to Australia’s role. It also exposes her to the risk Nauru may change the visa conditions affecting her freedom at any time and the use of physical force against her by Australia and its agents within the detention centre. In this regard it is to be noted Gordon J was not alone in her conclusion [Gageler and Bell JJ agreed] that, despite the administrative arrangements, the Commonwealth detained the plaintiff on Nauru.

The dissenting reasoning is to be preferred because it delimits the power of the State by reference to the purposes for which the power can be exercised – in this case for the removal of the subject from Australia – because it proposes a standard that can be effectively invoked, reducing the risk that the affected party – plaintiff M68 – must endure a regime from which lawful authority somehow falls away over an indeterminate period of time. The standard has teeth because it is more capable of providing a certain measure of the limits of State power directed to depriving a person of her liberty.

Umberto Torresi

February 2016

[1]Asylum Seekers (Regional Processing Centre)Act 2012 (Nauru)

[2] Transfield Services (Australia) Pty Ltd subcontracted its functions or some of them to Wilson Security Pty Ltd.