Omar Khadr, captured aged 15 by the US in Afghanistan, has left Guantanamo Bay for his native Canada after 11 years. There he is likely to remain in jail for a year, an echo of the treatment of Australian David Hicks. Khadr’s case shows the USA’s (and Canada’s) contempt for international law, writes Robert Briggs in his update on a 2010 article.

Omar Khadr, captured aged 15 by the US in Afghanistan, has left Guantanamo Bay for his native Canada after 11 years. There he is likely to remain in jail for a year, an echo of the treatment of Australian David Hicks. Khadr’s case shows the USA’s (and Canada’s) contempt for international law, writes Robert Briggs in his update on a 2010 article.

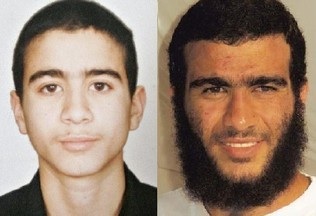

Photos: Khadr when arrested, and now.

h3>2012 Update:

The Canadian government obstructed the return of Omar to Canada for nearly a year after October, 2011, when he became eligible for return. On the last weekend of September of this year, Omar Khadr was repatriated to Canada, where he has six years “sentence” yet to serve. He will be entitled to parole next July, and it’s possible his remaining sentence will be struck down in light of earlier rulings by the Canadian Supreme Court concerning his Guantánamo imprisonment, interrogation and military trial. The court has steadfastly criticised the behaviour of Canada and its involvement in Omar’s ordeal, in violation of the Canadian Charter of Rights.

One reason that induced Omar Khadr (and David Hicks before him) to accept a plea deal was the very real danger that the US would continue to hold him prisoner, even if acquitted, based on a claim that he was still validly classified as an “enemy combatant,” or unprivileged enemy belligerent. The US maintains that status entitles it to hold a prisoner – even a civilian belligerent – until the end of the conflict.

That’s plain wrong, as the international director of Human Rights First, Gabor Rona, points out in a recent legal article http://jurist.org/hotline/2012/09/gabor-rona-ndaa-symptom.php:

The US chose to define "enemy combatant" to include what the law of inter-State armed conflict considers civilians as well as combatants. And to make matters worse, the US also decided to apply to this mélange those traditional detention standards meant only for combatants: the power to detain "until the end of hostilities." …. [but] as a matter of international law, civilians under traditional inter-State armed conflict rules may only be detained so long as they remain a security threat, even if hostilities continue.

In transplanting rules from where they belong to where they do not, the US not only misuses the law of war during conflict, it also, perhaps even more harmfully, applies the law of war to non-war. Armed with the rationale that old rules are inadequate for new conflicts, the US has sought to justify the application of expanded wartime rules to detain people outside the context of war. And within war, the US attempts to justify detention of civilians under broad powers meant for the detention of combatants.

…. At the same time, the US declines to import even the … meagre … substantive limitations and due process protections that the Geneva Conventions and customary international humanitarian law apply to targeting and detention, let alone applicable human rights law.

ORIGINAL ARTICLE: 29 OCT 2010

A US show trial has finally resulted in the citizen Canada abandoned, Omar Khadr, pleading guilty to a ‘war crime’ that wasn’t when he was kidnapped by the USA as just a child of 15. Now 24, he will stay jailed a few years more in a case similar to that of Australian David Hicks. CLA member Robert Briggs, a lawyer qualified in the US and Australia, analyses what the Khadr case means for the international rule of law. Photos: Khadr when arrested, and now.

Khadr: US changes rules of war

By Robert Briggs*

After spending a third of his life at Guantánamo, the Canadian Omar Khadr – aged 15 when arrested by the US military at a firefight in Afghanistan – has pleaded guilty before a military commission to five “war crimes”, including the “murder” of a US soldier.

Human Rights First observer Daphne Eviatar was there (article).

Much has been made of the fact that Khadr was a child of 15 when the events occurred, and should have been treated as a child soldier, but that argument misses the point. The most shocking aspect of the case is not Khadr’s age but this: it is now a “war crime” to oppose American forces in an occupied country. Never before in the modern history of armed conflict has a participant succeeded in making it a war crime to oppose its soldiers, where no treachery or illegal weapon was involved. International humanitarian law – the law of war – has been turned on its head.

Like the Australian David Hicks, Khadr will be returned to his home country to serve part of a legally-questionable sentence. Once in Canada, he may be able to have the sentence invalidated, although the Canadian government has proved as obdurate as the Australian government in its refusal to look after a citizen.

Now that it’s over, it’s time to look at all that was wrong in the case of Omar Khadr. It’s hard to know where to start.

The only circumstance suggesting a military offence even occurred is the fact that Khadr was taken prisoner in a theatre of war, during a war. In no other way does the case suggest a valid basis for a “war crimes” prosecution.

Here are some of the facts:

- None of the five alleged offences (murder/attempted murder in violation of the law of war, conspiracy, material support for terrorism, and spying), as they are defined and applied to Khadr, is a valid crime under the laws of war.

- Murder, conspiracy and material support were created by the US Congress in 2006 after the events they purport to criminalise. That’s a violation of the ex-post-facto clause of the US constitution, as well as international law.

- The Stipulation of Fact, which Khadr was required to sign, contained self-serving legal conclusions designed to give the commission jurisdiction it would not otherwise have.

- Although the US Supreme Court has invalidated some of the Military Commissions Act, the part containing the offences has not been judicially reviewed. A decision on the validity of conspiracy and material support is imminent in the appeals of the convicted defendants Salim Hamdan and Ali Hamza Al Bahlul, argued in January 2010 in the Court of Military Commissions Review. No appeal has progressed to Article III (civil) courts.

- Khadr was a child of 15 when the acts occurred, and under international law the “Child Soldier Protocol” protects him from prosecution for war crimes. Khadr was one of the few children held at Guantanamo who was not afforded separate quarters, education and protection as a child.

- Besides the substantive law, the procedures and rules of evidence in the military commissions do not meet the requirements of international law. The trial itself offends Common Art 3 of the Geneva Conventions, Article 75 of Protocol 1 to Geneva, and the International Covenant for Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR). The use of nonconforming military tribunals is itself a war crime, one for which the US prosecuted the Japanese after WWII.

- Other than Khadr’s coerced and recanted confessions (and now, his guilty plea), there is no evidence, physical or eye-witness, that Khadr threw a grenade or fired shots at US forces (both normal incidents of war) although the Pentagon admits altering reports that imply only Khadr could have thrown the grenade that killed one US soldier and injured another.

- If any violations of the law of war occurred at the firefight where Khadr was arrested, they may be those of the US, who fielded an unprivileged belligerent (a CIA operative), and shot Khadr twice in the back when he was hors de combat. The latter is a paradigmatic war crime.

- Khadr’s treatment after capture violated US law as well as multiple international treaty obligations of the US, eg the Geneva Conventions, ICCPR, and the Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CAT). He was improperly interrogated while wounded, removed from the theatre of war (arguably a war crime when the person is not a PoW) and abused, most likely tortured, at multiple locations including Guantánamo. His principal interrogator (later convicted by the US for abusing a prisoner who died) admitted threatening Khadr with tales of rape and death.

- Canadian federal courts, including the Canadian Supreme Court, have repeatedly ruled that Khadr’s rights have been violated, both by Canadian foreign and security services under the Canadian Charter of Rights and by the US.

- Khadr’s first military commission was thrown out when the US Supreme Court found the whole process unconstitutional.

- At Khadr’s second military commission, the presiding judge was removed and forcibly retired when he made rulings favourable to Khadr.

- The replacement judge in Khadr’s revived military commission ruled that none of Khadr’s confessions were inadmissible due to torture, although another child detainee, also accused of throwing a grenade and whose mistreatment was remarkably similar to Khadr’s, had his case dismissed by another judge. This detainee, Mohammed Jawad, was repatriated to Afghanistan.

How was it possible for such an overt miscarriage of justice to be carried out? One reason was the acquiescence of other countries, including the surprising collaboration of English common law democracies such as Australia and Canada.

More important, however, was the groundwork laid in the meticulous propaganda accepted – again surprisingly – by the media, foreign as well as American. Early on, the US government rigged the debate by twisting the language used to describe its acts and misrepresenting the law that applied.

`When I use a word,’ Humpty Dumpty said, in rather a scornful tone, `it means just what I choose it to mean – neither more nor less.’

Humpty Dumpty, in conversation with Alice, in

Through the Looking Glass, by Lewis Carroll

The media accepted, without question, most of the US government claims and assumptions, some backed up by dishonest “legal” opinions concocted by Justice Department and Pentagon lawyers.

These included claims that anyone could be seized, detained and interrogated by the US anywhere in the world if it is claimed to be for “intelligence”, and that “enemies” of the US anywhere could be subjected to military law, even if they are civilians, are not citizens of a country with which the US is at war, and may have been seized outside a time and/or place of war.

Under the Bush administration view, prisoners made subject to military law (and thus the law of war) could fall outside the Geneva Conventions, and be treated as the government pleased, not under the law of war. In the event the Geneva Conventions did apply, the US President could suspend them by unilaterally ruling they don’t apply (or conclusively determining he had complied with them). In fact, the treaties are part of American law and only Congress can derogate from them. No court precedent to the contrary exists, although the Justice Department’s notorious “torture memos” author, John Yoo, fabricated one.

It was argued that, in the event the Geneva Conventions applied, notwithstanding a presidential finding that they didn’t, the prisoner was still not entitled to an Article 5 hearing to determine if he was a PoW, nor was he entitled to the identical hearing set out in US law in Army Regulation 190-8, which likewise makes no provision for presidential determinations of enemy status.

By claiming prisoners were military rather than civilian criminals, the US claimed (and still claims, outside Guantánamo) that it could deny them lawyers and due process, and claim military necessity, even if far from any battlefield.

Without the recognition of the status of civilian criminal or prisoner of war, the US continues to claim that prisoners can be held indefinitely and interrogated without restriction for any reason, and punished or rewarded according to their answers. The media has never asked how this can be, since the Supreme Court ruled that, at the very least, Common Article 3 of Geneva applies. Moreover, why doesn’t Common Article 3 prevent non-conforming military commissions being held?

• Robert Briggs is a Canberra-based writer with Australian and US legal qualifications, and a member of CLA. He has followed the Guantánamo experiment since its inception and written about it since 2005.