By Mark Handler*

Book Review: ‘Wrongful Convictions and Miscarriages of Justice: Causes and Remedies in North American and European Criminal Justice Systems’ (Criminology and Justice Studies) edited by C. Ronald Huff and Martin Killias. ISBN-10: 0415539951 ISBN-13: 978

This US review, by a polygraph – “lie detector” – expert for a US industry magazine, covers one of the recent seminal books in the field of wrongful convictions (WCs) or Miscarriages of Justice (MOJs). AS the author says, his interest was piqued by the chance to explore better education of police…because that’s where most WCs and MOJs start.

As with other books on this subject for which I have written reviews, I point out my belief that polygraph examiners are in a unique position to curtail some of the practices that lead to these sad situations. Often the polygraph examiner is the first “neutral party” a criminal suspect encounters during an investigation. I have heard many a tale from the field from examiners who were asked to “get this guy to confess”, only to emerge from a test with non-deceptive charts.

One of the primary reasons this phenomenon occurs is because examiners are not (hopefully) relying on convention-based, error prone credibility assessment tools. Today’s examiners are using scientifically validated techniques that unyoke their decision making process from their “gut feelings” which perform at chance levels at best.

So why read these books, or study these errors? Because they help us continue to realize mistakes get made and remind us of the dire consequences. The 5th century BC. Chinese military strategist Sun-Tzu is credited with writing, “Know thy self, know thy enemy. A thousand battles, a thousand victories.”

So why read these books, or study these errors? Because they help us continue to realize mistakes get made and remind us of the dire consequences. The 5th century BC. Chinese military strategist Sun-Tzu is credited with writing, “Know thy self, know thy enemy. A thousand battles, a thousand victories.”

Wrongful convictions and miscarriages of justice are an enemy of a good criminal justice system. If we learn vicariously through the mistakes of others about this enemy, we can improve the system.

The book is divided into three sections, each containing a chapter or chapters related to that section. Section one is dedicated to considering the causes and frequencies of wrongful convictions. It includes ‘Wrongful Convictions in a World of Miscarriages of Justice’ by Brian Forst. This chapter describes different types of miscarriages and makes estimates of the magnitudes of each. Forst provides some thoughtful insight into the costs of these errors to the wrongfully convicted and to society as a whole.

Samuel Gross tackles a thorny issue of estimating the number of wrongful convictions that occur. He uses some clever approaches to estimate lower and upper bands of frequencies. I found it interesting how the results of several different methods tend to converge on the 3-5% range. If one were to multiply the total number of incarcerated people by 3-5%, the numbers (and cost) become staggering.

Martin Killias, one of the editors, looks at the differences between an accusatorial system (like the United States) and an inquisitorial system (such as found in Europe.) He compares and contrasts the pros and cons and shows that ultimately the accusatorial system results in more exonerations. He offers some insight into why moving towards a more inquisitorial model might reduce wrongful convictions.

One of the best chapters I found was one written by Brandon Garrett titled “Trial and Error”. Professor Garrett outlines some of the errors in the post-convicted exonerations he studied for his book. He writes that the evidence presented to the juries seemed solid at the time. Only through the hindsight of reviewing all the trial were the main categories of errors discovered.

They include; lying informants testifying, bad eyewitness identification procedures, poor police interview and interrogation practices, and bad lawyering from both the defense and prosecution side. He provides examples of each that will leave you shaking your head wondering how this could happen.

Prosecutor becomes judge…

Jim and Nancy Petro do yeoman’s work of explaining the prosecutor-wrongful conviction conundrum. The prosecutor is arguably the most powerful player in the criminal justice system. They decide who gets charged, what to charge, who gets a plea bargain offer, what type of offer they get, who gets investigated, who gets subpoenaed, and much more. Since 95% of criminal cases in the USA are resolved by plea bargain, the prosecutor becomes judge, jury and execution in most cases.

Jim Petro was the Attorney General of Ohio from 2003 through 2007. He became involved in the Innocence Project during that tenure when he came to the aid of a wrongfully convicted Clarence Elkins. Petro became dismayed at the tenacity with which the prosecutor in the case fought to keep Elkins’ defence team from reviewing his convictions. Despite DNA evidence excluding Elkins, the DA fought to sustain Elkins conviction. Elkins was eventually released but unfortunately while he was serving time the real culprit went on to commit three child rapes while innocent Elkins served time in prison.

Petro describes the great challenges prosecutors face from serving their constituents to serving the criminal justice system. Power can corrupt and absolute power can corrupt absolutely, as we see from a number of examples provided in the chapter. Finally, the Petros discuss recent changes to laws about prosecutorial immunity.

Simon Cole and William Thompson write a chapter on forensic science and wrongful convictions. Forensic science has contributed to wrongful convictions but it has also been used to expose them. DNA analysis has played a major role in identifying wrongful convictions and was the crack in the dam that forced the criminal justice system to confront this demon. For years’ cognitive dissonance kept many public safety officials from acknowledging the existence of wrongful convictions. Unfortunately, forensic science has been abused and overused and is one of the greatest contributors to wrongful convictions.

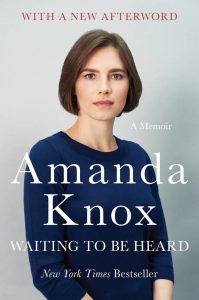

Vuille, Biederman and Taroni use the Amanda Knox “murder” case in Italy as a backdrop for discussing DNA profiling, and misunderstanding of scientific results. While no malfeasance may be intended, a lack of understanding or inability to explain scientific results can have disastrous outcomes. Triers of fact count on expert witnesses to help them understand scientific material to supposedly inform his or her decision-making processes. When those results are exaggerated, twisted, incorrectly conveyed, or – worse yet – manufactured, it corrupts the system.

Vuille, Biederman and Taroni use the Amanda Knox “murder” case in Italy as a backdrop for discussing DNA profiling, and misunderstanding of scientific results. While no malfeasance may be intended, a lack of understanding or inability to explain scientific results can have disastrous outcomes. Triers of fact count on expert witnesses to help them understand scientific material to supposedly inform his or her decision-making processes. When those results are exaggerated, twisted, incorrectly conveyed, or – worse yet – manufactured, it corrupts the system.

One of the more introspective contributions was Brants’ chapter on tunnel vision, perseverance and confirmation bias. Professor Brants used four major exoneration cases from the Netherlands as examples for these human decision-making heuristics. She does a nice job of breaking down each heuristic and citing real world examples. She offers some safeguards to help prevent them.

Aebi and Campistol have a chapter on the little discussed “voluntary” false confession that leads to wrongful conviction. Most false confession discussion centres on the coerced or pressurized compliant or internalized variants. These authors review research on the voluntary false confession. As could be predicted they mostly occurred to protect another person (juveniles or terrorist cases), though some occurred to promote legislative changes (assisted suicide, for example).

Kathryn Campbell pens a short chapter on preventive detention following the 9/11 tragedy. She discusses wrongful detentions associated with suspected terrorists in the United States and Canada. I found this an interesting chapter where one contemplates individual liberty versus national security interests.

Whatever side of the fence you find yourself on in this debate, the “War on Terror” is not over. We can probably benefit from a hindsight review of the actions we took. Which actions worked (and should be kept), which did not and should be abandoned.

The most eye-opening chapter was the concluding one in Part 1, Gwladys Gillieron on Plea Bargains in the United States and Summary Proceedings in the European model.

In 2010, more than 97% of state and federal criminal cases were resolved through plea bargaining in the United States. In Europe the percentage was slightly less (around 90%) but still staggering. If one were to think about the number of criminal cases in the United States alone, 97% being “settled” sets a stage fraught with the potential for a wrongful conviction. Especially when one considers that in the United States it is legal to threaten more severe consequences should a subject be found guilty, after deciding to go to trial versus plea bargain (Bordenkircher v. Hayes, 1978:363). There is an obvious concern that an innocent person would take the offered deal rather than run the risk of a much harsher sentence. Add to this that most states and the federal system, require a defendant to waive their right to appeal as a part of the plea agreement.

Part 2 centres on consequences and remedies for wrongful convictions. One of the more disturbing chapters was Westervelt and Cook’s examination of the aftermath of a wrongful conviction. Most of us believe in a fair world and probably just assume that exonerees are adequately compensated and helped to reintegrate into society. Unfortunately, the truth is many are not.

Based on in-depth interviews with 18 death row exonerees, the authors paint a very tragic picture of lives shattered and for the most part irreparable. They have an immediate problem of securing a place to live, food, medical care, transportation, learning new technologies, living outside of a prison environment, and much more. For the most part they all reported their familial relationships ruined, non-existent or difficult at best. Most were diagnosed with some degree of post-traumatic stress disorder that severely impairs their ability to start life over.

Kent Roach writes a chapter on remedies for wrongful convictions in the United States and Canada. His thesis is that Canada provides fewer formal legal remedies for wrongful conviction, but is more amenable to considering new evidence in these cases, than is the United States. He argues the United States system often demands a proof of actual innocence, in addition to the additional evidence. This proof requirement makes the prospect of a new hearing in the United States less likely. The chapter is a really good primer for learning about the post-conviction relief appeals process in both countries.

Lappas and Loftus offer a chapter on “The Rocky Road to Reform – State Innocence Studies and the Pennsylvania Story. They use the plight of wrongfully convicted Thomas Doswell as the backdrop for describing Pennsylvania’s state Senate’s attempt to create an advisory committee to study the underlying causes of wrongful convictions. This committee became a battleground where law enforcement and prosecutors fought with the other members over reform recommendations. The Pennsylvania District Attorneys Association took an active role against the work of the committee.

Challenges to reform

In September, 2011, the committee produced a 316-page report detailing its findings and recommendations for reform. Two hours later the Pennsylvania District Attorneys Association released their own report condemning the Advisory Committee report. Given the enormous power of district attorneys, without their support the recommendations of the advisory committee were likely to fall on deaf ears.

There is a small chapter on a man named Edwin Borchard, written by Marvin Zalman. Borchard is often cited as one of the early scholars who wrote about wrongful convictions.

The final chapter of Part 2 is Ronald Huff’s discussion on challenges to reform. He starts by stating the following about the first 301 post-conviction DNA exonerations:

- Eighteen of the 301 were sentenced to death.

- The average time served before exoneration was about 14 years.

- About 70% of these exonerees were people of colo

- DNA identified the actual perpetrator in about half of these cases.

- People have been exonerated in 35 states and the District of Columbia.

These cases are only the ones for which we had DNA to exonerate them, a point Roach makes when calling them “the tip of the iceberg”. About 90-plus per cent of criminal cases do not have DNA to examine. Roach describes the aftermath of two sensational cases:

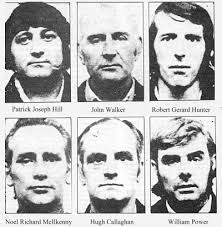

- “The Guilford Four” from the 1974 bombing of two pubs in Guilford, England spent up to 15 years in prison before being found innocent and released.

- “The Birmingham Six” – Hugh Callaghan, Patrick Joseph Hill, Gerard Hunter, Richard McIlkenny, William Power and John Walker—sentenced to life imprisonment in 1975 in England for the Birmingham pub bombings. Their convictions were declared unsafe and unsatisfactory and quashed by the Court of Appeal on 14 March 1991 after serving up to 16 years in prison.

A forensic psychiatrist, Adrian Grounds, conducted clinical assessments of the 11 wrongfully convicted who served prison terms ranging from 4 to 16 years (mean = 12). On the average they were 30 years old when they went to prison and 42 upon release. He describes his assessment as “wholly unexpected”. He reports patterns of severe psychological problems that disabled these people from living normal lives. He said they were similar to former hostages and survivors of natural disasters.

A forensic psychiatrist, Adrian Grounds, conducted clinical assessments of the 11 wrongfully convicted who served prison terms ranging from 4 to 16 years (mean = 12). On the average they were 30 years old when they went to prison and 42 upon release. He describes his assessment as “wholly unexpected”. He reports patterns of severe psychological problems that disabled these people from living normal lives. He said they were similar to former hostages and survivors of natural disasters.

He described enduring personality changes including; estrangement, loss of a capacity for intimacy, moodiness, inability to stabilize, loss of sense of purpose and a loss of initiative and direction. Most were diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder. Many of the immediate families also suffered significant psychological problems related to their wrongful incarceration. The documented human suffering from these two cases alone should give us cause to pause and figure out lessons learned to hopefully reduce a chance of repeating the errors.

Part 3 is a one-chapter conclusion and recommendation chapter by the editors. Killias and Huff review;

- What is a “wrongful” conviction and how to use a thoughtful consideration of “wrongful” to expand our thinking about these errors.

- Estimating the enormity of the problem. Even if we get 97% of the cases right, that still leaves a lot of potential for innocent people to lose their liberty.

- A summary of our current knowledge of the causes of wrongful convictions and some potential remedies to reduce these.

- The role of the most important players in the criminal justice system, the prosecutors. Only with prosecutorial consideration will these reforms be effective. Criminal justices systems have developed such that the prosecutors are in THE key role to help institute reforms that will work.

- Consequences of the wrongful convictions to both the exonerees and society as a whole. When a person is wrongfully convicted, the real “bad guy” gets away and often does more harm on society. Also the cost to the families of the exonerees should be considered when weighing pros and cons of reform.

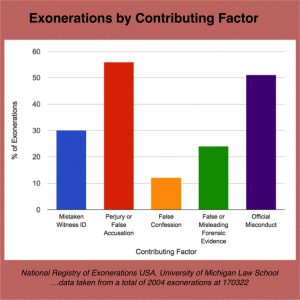

Finally, they close with possible remedies to begin to reform the parts of the criminal justice system that are most likely related to wrongful convictions. The major sources (the Big Three) are; using jailhouse informants, contaminated confessions and eye-witness misidentification. Others do contribute (bad lawyering by either prosecutors or the defence attorney) but the Big Three are responsible for the “lion’s share” of the errors.

Ultimately they close the book with the recommendation that made me pick the book up in the first place: education of police officers to improve their professional performance. They note that professional law enforcement officers are often one of the first to embrace positive change.

As a polygraph examiner you probably have found yourself (or inevitably will be) placed in an uncomfortable position where you have to provide your consumer with “bad news”. That news being this person’s test result is inconsistent with their expectations. While it is “only” a test result, we should remember it is still the best test available for veracity assessment. Many of you are functioning daily in law enforcement and get to have an impact on the outcome of the investigation. I don’t doubt that most agencies have excellent investigators referring your cases. But sometimes, just sometimes, they are victims of human decision making heuristics that create tunnel vision. By having some understanding of when, where, why and how things can go wrong you are a wiser advocate for them, for your agency and for society. In closing I highly recommend this book to anyone who has the potential to come into contact with anyone facing a potential incarceration.

Note: This review was originally published in ‘Polygraph’ 2016, 45 (1).

* Mark Handler is an independent polygraph instructor and consultant. He serves on the board of the American Polygraph Association (APA) and American Association of Police Polygraphists (AAPP). In the past, he was a Deputy Sheriff in Conroe County, Texas, and a US Navy nuclear submariner. Mark previously served on the advisory board of Converus, a US polygraph manufacturer, for whom is now Director of Technical Services.

* Mark Handler is an independent polygraph instructor and consultant. He serves on the board of the American Polygraph Association (APA) and American Association of Police Polygraphists (AAPP). In the past, he was a Deputy Sheriff in Conroe County, Texas, and a US Navy nuclear submariner. Mark previously served on the advisory board of Converus, a US polygraph manufacturer, for whom is now Director of Technical Services.