By Kay Danes, OAM

Beware Australia’s Defence Forces: they kill.

But who are they killing more of, the enemy…or their own people?

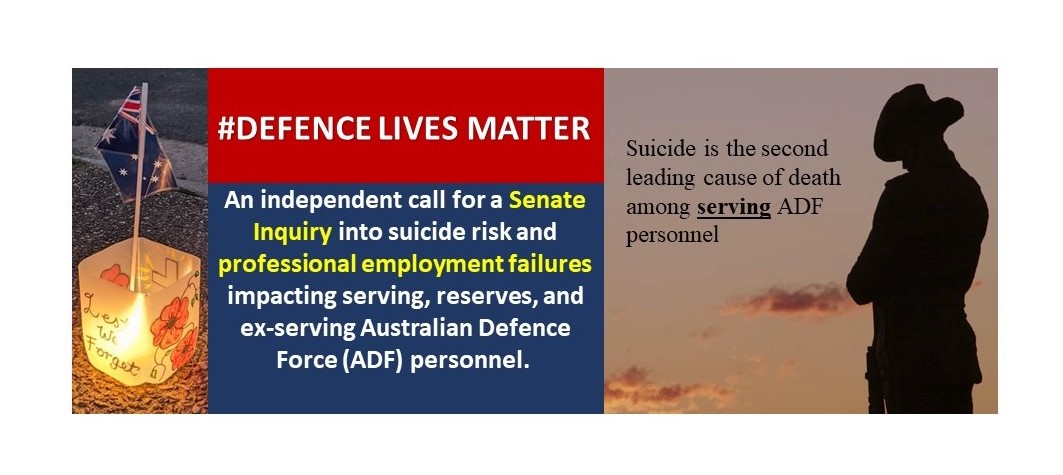

Suicide is the second leading cause of death among serving ADF personnel and the leading cause of death among ADF reserves and ex-serving ADF personnel.[1]

Current research into the organisational practices of the ADF suggest a connection between military service and institutional harm that ‘links an unyielding bureaucracy of the ADF and Department of Veteran Affairs (DVA) to Veteran suicide, ‘further suggesting that ‘suicide and self-harm among [ADF personnel] and veterans have become endemic in recent decades.’[2]

Between 2002 and 2015, there were close to 2,000 deaths of men and women with at least 1 day of ADF service. (At face value, this is about double the rate of deaths of Indigenous people, over the same period, which were likely caused by institutional issues).

For men in the ADF, 52% (929) were ex-serving at time of death, 26% (468) were in the reserves and 22% (393) were serving full time. Of this number, there were 325 certified suicide deaths among people with at least 1 day of ADF service since 2001. Of these, 50% (166) were ex-serving at the time of their death, 28% (90) were serving full time and 21% (69) were in the reserves.[3]

ADF personnel who are medically discharged are 1.9 times more likely to suicide than those who discharge voluntarily.[4]

In 2018-19, the Inspector General of the ADF (IGADF) independently reported 31 deaths of ADF personnel, of which 19 (40%) were suicide related.[5] The IGADF report confirmed the connection between suicide risk and complaints relating to Professional Employment Failures (41%).

In other words, Management Initiated Early Retirements, Redress of Grievances complaints, or detriments caused by Defective Administration[6] have the greatest potential to expose serving, reserves and ex-serving ADF personnel to suicide risk, self-harm or to cause them to want to harm others.[7] Other causes were identified as a result of termination of service (39%) and entitlements (11%). Incidentally, the Australian Army has a disproportionate amount of suicides among serving, reserves and ex-serving ADF personnel, compared to the other armed services.[8]

Clearly, continuing this rate of death of Australia’s service personnel cannot be tolerated. The government must act positively and quickly to stop this waste of Defence lives.

Normal ‘legal’ rules don’t apply: justice concepts are missing

Previous studies have shown that a common denominator of suicide risk is connected to professional employment failures that generally occur during Defence Inquiries under the Defence (Inquiry) Regulations Act 2018.

On paper, the purpose of a Defence Inquiry is to assist command in securing the proper functioning of the ADF by providing the most important enabler of a good decision—accurate, reliable and timely information.[9] It is, however, now commonly recognised within the ADF serving community that internally-conducted Defence Inquiries – where a hierarchy of legally unskilled officers act as judge and jury over complaints – expose ADF personnel to injustice, and exacerbate serious distress, depression, and suicidality.[10]

Studies have shown that ‘those responsible for the mismanagement of allegations of abuse, have not been identified, called to account or rehabilitated and these persons have often advanced to more senior positions in the ADF.’[11]

In this context, ADF personnel who are selected to conduct a Defence Inquiry into allegations of abuse are generally chosen on the basis that they have ‘appropriate management and/or research and analytical skills, communication and report writing skills.’[12] Some are provided four days of non-mandatory training. They are not required to be legally trained. They are not bound by the rules of evidence, legal norms or technicalities and are not constrained by the fundamental concepts of justice and equality.

Previous complaints have argued that witnesses have provide false testimony but are protected by legal privilege and ‘administrative action should not be progressed on the basis of unsworn evidence.’ [13] This recommendation was previously denied on the basis that ADF policy state that any person who wilfully gives false evidence to a Defence Inquiry is subject to prosecution for an offence under the Defence (Inquiry) Regulations Act 2018. Civilians, however, cannot be prosecuted under either the Defence Force Discipline Act 1982 or the Defence (Inquiry) Regulations Act 2018. This rule also applies to those who may have initially lodged a complaint while serving but have since been discharged from the ADF for a period of six months.

Defence Inquiries are supposed to be timely but seldom are. They are also very costly to the Australian taxpayer. As at 30 June 2019, the IGADF staffing numbers totalled 103 personnel (42 permanent staff) and (61 Reserve personnel). In this period, five professional service providers were engaged to undertake inquiry work. A further six delivered a range of services including legal expertise. The cost to the Australian taxpayer for these cases alone is representative of millions of dollars.[14]

In 2017, the ADF was forced to pay the legal expenses of one of its former employees to the amount of $1 million dollars.[15] The Department of Veteran Affairs paid over $15 million dollars securing high level legal firms to fight compensation claims by veterans.[16]

These examples suggest that to have any reasonable opportunity to lodge a defence against an injustice, serving, reserves and ex-serving ADF personnel must first have significant financial resources to even present a complaint to the ADF.

Unfortunately, most serving ADF personnel fight behind closed doors and are often crippled against the might of Defence legal resources that are effectively used to counter their complaints. Those that do manage to slip through the cracks, believing they will secure justice with the help of the Commonwealth Ombudsman, are frequently disappointed to learn that the Defence Watchdog consistently defaults to the pre-adopted position of Defence: ‘We know the Ombudsman and the Inspector General of the ADF side with the Defence. There has never been a case where either have found against Defence.’[17]

‘Long legacy of inquiries that go nowhere’

Defence Inquiries are, therefore, ineffective as a mechanism for rooting out maladministration, a point that has long been argued in research: ‘the ADF has a long legacy of inquiries that go nowhere’ and ‘Veterans do not trust the ADF to act with integrity and transparency towards its own people.’[18]

What this means for ADF personnel is that they really have limited avenues to properly redress grievances. They see higher-ups perpetrate, idly witness, or fail to prevent acts that transgress the ADF person’s own moral and ethical values or codes of conduct…as well as those of the ADF. Such practical and emotional discord is a debilitating development inside institutional living and working. People believe they can no longer live full and healthy lives, because the rules and standards the ADF promulgates, which they thought they could rely on, are arbitrarily cast aside.[19]

Moral injury – an old enemy evolving to significantly harm serving ADF personnel

Many ADF personnel feel they have lost the ability to secure a fair and equitable hearing of their complaint and are morally injured. In the past, a moral injury was viewed as a condition that only impacted ADF personnel returning from war, and where a blind eye was frequently turned to rules and regulations.

Today, moral injury can also result in a ‘closed culture, where input from the outside is strongly resisted and where there is very little transparency within the organisation.’[20] The ADF is such a culture according to a Senate inquiry that suggested that ‘the Defence Force … cannot investigate itself on the one hand and defend itself on the other. This simply cannot be done fairly, without bias, thoroughly or properly.’ [21]

Research indicates that a total of 1,016 complaints from serving ADF personnel were made to Defence in 2018-19, an increase of 240 cases from previous years (a leap of nearly 25%). The Australian Army, in particular, has the highest number of complaints of unacceptable behaviour (e.g., bullying and harassment) in the workplace.[22] Defence attributes this increase to ‘a growing confidence of personnel in calling out and reporting unacceptable behaviour.’[23]

The number and nature of complaints, however, tell a different story. In 2018-19, the IGADF reported that its office maintained a consistently high tempo in responding to increases in submissions relating to investigation, inquiry and grievance complaints. ADF personnel submitted 360 Redress of Grievance complaints to the IGADF. By far the largest number of complaints, and rising, were from serving personnel representing the Australian Army.[24]

The Defence Force Ombudsman reported in 2018-19 that it had received a total of 1,101 complaints relating to termination, separation and transition, service delivery, redress of grievance, and Defence force recruiting.[25] The Ombudsman referred to 482 abuse cases of sexual abuse, serious physical abuse or serious bullying or harassment, where again the highest number of complaints were recorded against the Australian Army.

Other studies have also shown that complaints that relate to Defence administrative/legal issues and workplace difficulties are common psychological factors associated with increased suicide risk among serving ADF personnel.[26]

Systemic failures in ADF result in repeated demands for Royal Commissions

The systemic failures of the ADF in handling complaints also abound throughout the ADF Veteran community. Many reserve and ex-serving ADF personnel who had been forced out of the ADF through involuntary discharge, unfortunately succumbed to mental illness. More recently, their deaths have resulted in ongoing public appeals to establish a Royal Commission into ADF Veteran suicides[27] and prompted the Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison to appoint an independent commissioner to investigate the tragic epidemic of suicide within Australia’s defence forces.[28]

Clearly Defence Lives Matter but those signing petitions for Royal Commissions do so without knowing what the actual suicide risk is, in terms of serving ADF personnel, and particularly those who continue to suffer significant mental injuries when raising complaints of professional employment failures while still in service.

To date there has only ever been limited resources applied to these issues, and certainly no concentrated focus on either suicidal or homicidal ideation of serving ADF personnel.[29]

This represents a significant gap in research and a failure in getting to the root cause of serving ADF personnel suicide risk. Arguably, this type of research is critical, particularly since victims of professional employment failures remain in the workplace with their abusers while investigations are occurring. In many cases, the victimisation of serving ADF personnel is overlooked, disregarded and even admonished when complaints are pushed beyond the Chain of Command to the Ministerial level.

# Defence Lives Matter represents an independent call for a Senate Inquiry into suicide risk and professional employment failures impacting serving, reserves, and ex-serving Australian Defence Force (ADF) personnel.

Please sign the Petition:

https://www.change.org/defencelivesmatter

Visit the Website: www.defencelivesmatter.com

Open Arms – Veterans and Families Counselling provides support and counselling to current ADF members, veterans and their families, and can be contacted 24/7 on 1800 011 046.

Open Arms – Veterans and Families Counselling provides support and counselling to current ADF members, veterans and their families, and can be contacted 24/7 on 1800 011 046.

* The author, Kay Danes OAM, is a long-standing ADF Veteran’s Advocate and advisor to several ADF and Family Welfare Organisations. She is the wife of SAS Veteran Kerry Danes. Kay has a Masters degree in Human Rights (2015) and completed her PhD in the School of Law & Justice at Southern Cross University (April 2020).

Danes, K. 2018. ‘Command Failings that are defence-less’ CLArion.

Danes, K. 2016. ‘The Moral Ethic of ADF Employment Rights,’ CLArion.

Danes, K. 2019. ‘Army ‘Regs’ lead to institutional abuse by Defence’ CLArion.

Article References:

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, (2018). ‘Causes of death among serving and ex-serving Australian Defence Force personnel 2002–2015.’ (Report) Retrieved 07 June 2020 from https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/3e2b9b2e-937d-48cb-a5e9-c69814284d91/aihw-phe-228.pdf.aspx?inline=true ↑

- Effie Karageorgos, 2018. ‘An urgent rethink is needed on the idealised image of the ANZAC digger’. The Conversation. (21 November 2018) Retrieved 07 June 2020 from https://theconversation.com/an-urgent-rethink-is-needed-on-the-idealised-image-of-the-anzac-digger-107003 ↑ Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, National suicide monitoring of serving and ex-serving Australian Defence Force personnel: 2019 update, (Web Report) 29 November 2019 at https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/veterans/national-veteran-suicide-monitoring/contents/summary ↑

- Incidence of suicide among serving and ex-serving Australian Defence Force personnel (Detailed analysis) 2001–2015. See section: Modelling suicide risk (64). Retrieved 07 June 2020 from https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/f8bacce8-e12b-4c14-a789-ed2b292b7678/aihw-phe-218.pdf.aspx?inline=true ↑

- Inspector-General of the Australian Defence Force, 2019. ‘Annual Report – 01 July 2018 to 30 June 2019.’ Retrieved from https://www.defence.gov.au/mjs/_Master/docs/IGADF-Annual-Report-2018-19.pdf ↑

- Australian Government, 2020. Scheme for Compensation for Detriment caused by Defective Administration (CDDA Scheme), Department of Finance. Retrieved 07 June 2020 from https://www.finance.gov.au/individuals/act-grace-payments-waiver-debts-commonwealth-compensation-detriment-caused-defective-administration-cdda/scheme-compensation-detriment-caused-defective-administration-cdda-scheme↑

- Kay Danes, 2019. ‘ The Clarion. Council of Civil Liberties Australia. 08 August 2019. Retrieved from https://www.cla.asn.au/News/army-regs-lead-to-institutional-abuse-by-defence/#gsc.tab=0.↑

- Australian Government, 2001-2015. ‘Incidence of suicide among serving and ex-serving Australian Defence Force personnel.’ Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (Detailed Analysis). Canberra, Australia. pp133. Retrieved: https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/f8bacce8-e12b-4c14-a789-ed2b292b7678/aihw-phe-218.pdf.aspx?inline=true ↑

- Australian Government, 2020. ‘Inquiry Home.’ Retrieved https://www.defence.gov.au/Publications/COI/ ↑

- Mike Head, 2019. Lawyer charged for exposing Australian war crimes in Afghanistan.’ World Socialist Website. Retrieved 07 June 2020 from https://www.wsws.org/en/articles/2019/03/11/sasc-m11.html↑

- Commonwealth of Australia, 2013. ‘Report of the DLA Piper Review and the government’s response’ 27 June 2013. ISBN 978-1-74229-892-4. Retrieved from https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/Senate/Foreign_Affairs_Defence_and_Trade/Completed_inquiries/2010-13/dlapiper/report/index↑

- Kay Danes, 2019. ‘ The Clarion. Council of Civil Liberties Australia. 08 August 2019. Retrieved from https://www.cla.asn.au/News/army-regs-lead-to-institutional-abuse-by-defence/#gsc.tab=0.↑

- Australian Senate Committee, 2019. ‘Report on Military Justice Procedures in the ADF.’ Chapter 5, Administrative Action)Retrieved from https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/House_of_Representatives_Committees?url=jfadt/military/mj_ch_5.htm ↑

- Inspector-General of the Australian Defence Force, 2019. ‘Annual Report – 01 July 2018 to 30 June 2019.’ Retrieved from https://www.defence.gov.au/mjs/_Master/docs/IGADF-Annual-Report-2018-19.pdf ↑

- Luke Cooper, 2017. ‘It Took A ‘Demoralising’ Eight Years, But Finally This Former SAS Trooper Has Had His Service Recognised.’ 24 March 2017. Retrieved from https://www.huffingtonpost.com.au/2017/03/23/former-sas-trooper-evan-donaldson-has-service-recognised-after-e_a_22009628/

- Daily Telegraph. (15 July 2019) Retrieved from https://www.dailytelegraph.com.au/news/nsw/department-of-veterans-affair-spend-15-million-on-top-lawyers-to-fight-compensation-claims/news-story/5860bcae04761d830634a7235368f17b ↑

- Anonymous, 2020. Australian Defence Force personnel. ↑

- Ben Wadham and Deborah Morris, Enough inquiries that go nowhere – it’s time for a royal commission into veteran suicide. The Conversation. 06 August 2019 at https://theconversation.com/enough-inquiries-that-go-nowhere-its-time-for-a-royal-commission-into-veteran-suicide-119599 ↑

- The Moral Injury Project, Syracuse University, USA (2020) at https://moralinjuryproject.syr.edu/about-moral-injury/ ↑

- Tracey Emmott. Examples of institutional abuse and how to speak out about it. Emmott Snell Solicitors. 27 June 2017. Retrieved from https://www.emmottsnell.co.uk/blog/examples-of-institutional-abuse ↑

- Senate Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade References Committee, Parliament of Australia, The Effectiveness of Australia’s Military Justice System (16 June 2005). Retrieved from https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/Senate/Foreign_Affairs_Defence_and_Trade/Completed%20inquiries/2004-07/miljustice/report/index ↑

- Australian Government, 2018. Department of Defence. Workforce Summary. Chapter 8 – People. Unacceptable Behaviour at http://www.defence.gov.au/annualreports/13-14/part-three/chapter-eight.asp ↑

- Department of Defence, 2018. Annual Report 2018-19. Retrieved 03 June 2020 from https://www.transparency.gov.au/annual-reports/department-defence/reporting-year/2018-2019-62 ↑

- Inspector-General of the Australian Defence Force, 2019. ‘Annual Report – 01 July 2018 to 30 June 2019.’ Retrieved from https://www.defence.gov.au/mjs/_Master/docs/IGADF-Annual-Report-2018-19.pdf ↑

- Commonwealth Ombudsman, 2019. Office of the Commonwealth Ombudsman Annual Report 2018-19. Retrieved 03 June 2020 from https://www.transparency.gov.au/annual-reports/office-commonwealth-ombudsman/reporting-year/2018-2019-15 ↑

- Uniformed Services University, 2020. ‘Suicide in the military.’ Article released by the Centre for Deployment Psychology, United States. Retrieved 07 June 2020 from https://deploymentpsych.org/disorders/suicide-main ↑

- Julie-Ann Finney, ‘A Royal Commission into the Veteran suicide rate in Australia’ petition at https://www.change.org/p/a-royal-commission-into-the-veteran-suicide-rate-in-australia

- Kelly Burke, 2020. Veteran suicide inquiry called following death of Navy officer David Finney. 7 News. 05 February 2020. Retrieved 07 June 2020 from https://7news.com.au/lifestyle/health-wellbeing/veteran-suicide-inquiry-called-following-death-of-navy-officer-david-finney-c-681399

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2020. ‘Our Management Team.’ Australian Government. Retrieved 07 June 2020 from https://www.aihw.gov.au/about-us/our-people-structure/our-management-team

My research into suicide of returning WW1 veterans reflected the same results. Although my grandfather did not suicide he was a machine gun technician in the 1st Australian Machine Gun Battalion. Necessarily trained by British Machine Gun Command back then I found it quite shocking these men were known as “The Suicide Club”.

He supposedly had “shell shock” for the remainder of his life and passed away in Rockhampton General Hospital in January 1932 from Nephritis or severe kidney failure. I believe from his military medical records he was battling this illness during his service.

I applaud the efforts of all involved in bringing any injustice by our institutions to light. Thank you.

Defence lives matter help prevent further loss of lives…A royal commission into the matter is need