By CLA Vice-President Rajan Venkataraman*

Civil Liberties Australia has for a long time campaigned for the inalienable rights of prisoners and their just and humane treatment.

We do this for two reasons. We care about the human rights of prisoners (several prisoners currently serving time in Australia are members of CLA). We believe that enlightened policies on crime prevention and rehabilitation make the community safer.

Locking people away IS a punishment. But, equally, jails are meant to be places where rehabilitation happens: prisoners can take the time to gain skills they never got (like reading and numbers), gain a TAFE qualification, go through counselling and drug and alcohol treatment, and learn how to avoid criminal behavior in future.

Most – probably greater than 99.5 per cent – of prisoners simply want to ‘do their time’ and get out and go home to their family, friends and community. They don’t want to be in jail … but, increasingly, jail is where more people are.

Prison population rapidly growing

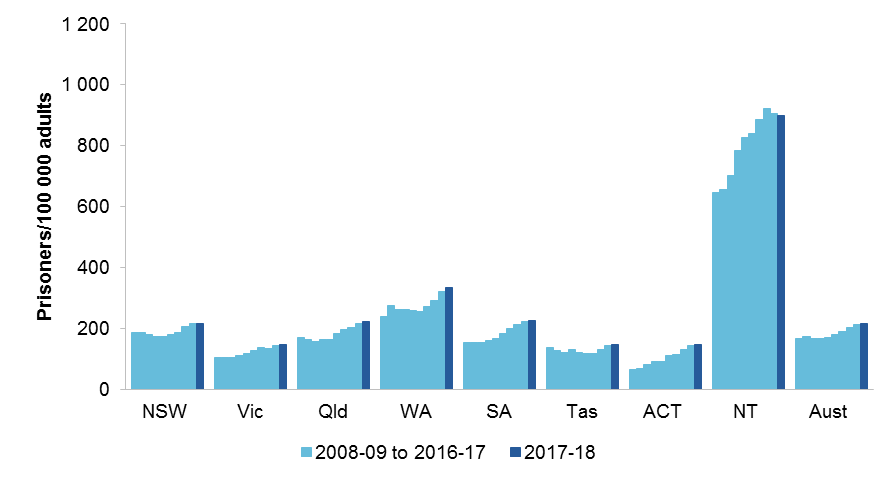

The rate of imprisonment in Australia has been growing rapidly over the past decades, even though actual crime rates have fallen[1]. We currently have around 43,000 people in 118 prisons, or around 221 out of every 100,000 adults in Australia. Federal MP Andrew Leigh calculates this is the highest rate of incarceration since the 1800s, leading him to dub this “the second convict age”.[2]

Australia’s rate of imprisonment is higher than most other developed countries. And, while other developed countries – even the US – are adopting policies to reduce prisoner numbers, the rate in Australia continues to grow. This is making overcrowding in prisons worse and forcing some states and territories to build more and/or bigger prisons.

There are better ways

In Australia, it has been politically popular for governments to be “tough on crime” by adopting policies to lock up more people, for longer periods, and for a greater range of offences. Politicians describe these policies as “keeping the community safe” despite the fact that they do no such thing.

Every serious analysis by academics, NGOs and parliamentary committees has shown that more imprisonment does nothing to reduce crime in Australia. In fact, it does just the opposite. Imprisonment, the conditions in prisons, and the difficulties prisoners face in reintegrating into the community after their release, lead to more criminal activity, not less. Meanwhile, suicides and assaults on both prisoners and prison officers continue to be common in prisons across Australia[3].

Overcrowding, under-resourcing, and pressures on staff numbers and training further undermine programs in prisons aimed at rehabilitation. The latest figures (2017-18) show that, nationally, 45.6 per cent of released prisoners (or nearly half) returned to prison within two years. This was up from 39.5 per cent in 2011-12[4].

A far better political approach would be for governments to pursue policies that are “smart on crime” (as well as cheaper – and better – for taxpayers). It’s actually possible to achieve that outcome.

A key part of a “smart on crime” approach would be to reduce significantly the number of non-violent offenders in our prisons through the increasing use of community corrections. At less than one-tenth the cost of keeping someone in prison, community correction has been shown to be an effective and economical way of dealing with non-violent offending[5].

Furthermore, to reduce offending in the first place, justice reinvestment[6] is an alternative approach where governments work with communities and organisations on early intervention to prevent crime and divert people away from the criminal justice system. Justice reinvestment has been shown to be effective – including in large-scale pilot studies around Australia.

It appears to be particularly effective where Indigenous imprisonment is high. Indigenous people are jailed at roughly 15 times the rate you would expect, given their numbers in the general population. In the NT, Indigenous jailing is a major societal issue.

Reference: Figure 8.1, ROGS report-2019-part c-chapter 8[7] …

Governments starting to listen

Governments around Australia have been stubborn in their pursuit of “tough on crime” policies despite the mounting evidence against them.

CLA has made numerous submissions on proposed changes to laws regarding bail, remissions, mandatory minimum sentences, suspended sentences, etc with a view to keeping people out of prison where possible, keeping children out of the criminal justice system, reducing the number of people in detention who have never been convicted of a crime, committing to justice reinvestment, and addressing the appalling rates of detention of Indigenous people.

There are signs though that governments may be starting to reconsider their policies. Why? Because of the costs to their budgets, and the burden on individual taxpayers.

The human costs of imprisonment are huge in terms of the impact on people’s lives, on their future employment, on their families and on communities.

But, just narrowly counting the cost of running our prisons, Australia spends around $5 billion a year on prisons – more than $300 per prisoner per day[8]. And the spending on prisons is growing faster than the growth in spending on most other areas of government activities (eg health, education, childcare)[9].

Governments are having to set aside large amounts in their budgets for new investments in prison infrastructure. Around the states, the Victorian Parliament recently released a report pointing to an “incarceration crisis” in that state driven by the number of people on remand (that is, people who are awaiting trial and have not been convicted of any crime)[10].

In NSW, the government Audit Office reported that the state’s prison population had grown by about 40 per cent between 2012 and 2018, and that the Department of Justice had responded by doubling-up and tripling-up the number of prison beds in cells, reactivating previously closed prisons, and investing around $3.8 billion in new prison capacity[11].

In the ACT, the Inspector of Prisons recently reported on the poor conditions and overcrowding at prisons there[12]. In Tasmania, the Auditor General released a report about significant cost blow-outs and under-resourcing in the prison system driven by recent government policies[13]. And the Tasmanian community has come out strongly against a proposed new prison in the north of the state.

Perhaps the most significant development has been the inquiry by the Queensland Productivity Commission into imprisonment and recidivism[14]. This inquiry is charged with taking an evidence-based approach to examining alternatives to imprisonment aimed at addressing the growth in prisoner numbers there.

What CLA is doing

CLA believes that the current crisis in prisoner numbers in Australia presents an opportunity for real change in government policies. We are working on a number of initiatives.

Queensland inquiry report due

CLA made a substantial submission to the inquiry by the Queensland Productivity Commission into imprisonment and recidivism. The inquiry report is due for release in early 2020. We will be pushing for the Queensland Government to implement the recommendations of the inquiry. And we will be pushing for other states and territories to implement any recommendations that are relevant to them … as most probably will be.

Raising the age of criminal responsibility

In Australia, a child as young as 10 can be charged with a crime, ensnared in the criminal justice system, and even imprisoned.

Treating children so young as criminals puts Australia out of step with most developed countries (and in fact most countries, full stop). We are pushing federal and state governments to raise the age of criminal responsibility to at least 14. Governments have been dragging their feet on this despite appalling revelations about the treatment of children in Australian prisons.

Effective implementation of OPCAT

After a lot of pushing by CLA and other organisations, the Australian Government finally ratified the Optional Protocol to the Convention Against Torture and is starting to implement it around all the states and territories.

OPCAT puts in place a system of independent monitoring of places of detention. We are continuing to work with other organisations to ensure independent monitoring in Australia is effective and that governments respond promptly to the findings of the monitors.

The right to vote of prisoners

Around Australia, different rules apply to the voting rights of prisoners. In federal elections, people serving full-time prison sentences of more than three years are not entitled to vote. The same three-year rule applies in Tasmanian and NT elections. In Victoria there is a five-year rule, but in NSW and WA there is a more restrictive one-year rule.

Queensland has the most restrictive rule of all. Queensland prisoners are denied the right to vote in their state and local elections regardless of the length of their sentence.

SA and the ACT have the most open rules. All prisoners can vote in state and local elections there.

There is no rhyme or reason behind this patchwork of rules in Australia. CLA’s view is that there is no reason why imprisonment – regardless of the length – should mean a loss of voting rights. This disenfranchisement is a penalty over and above the sentence imposed by the judicial system.

And with Indigenous people around 15 times more likely to be imprisoned than non-Indigenous people, the overall effect is hugely discriminatory. CLA will be pushing for reforms in this area.

Censoring reading matter puzzle

Prisoners are routinely denied access to publications and printed materials in a form of “walled censorship”.

These decisions made by prison authorities are quite arbitrary. It is not clear what criteria are being applied, under what laws these restrictions are being applied, and who is authorised to make these decisions.

These arbitrary decisions deny prisoners legitimate contact with the outside world and in many cases deny them access to educational and other materials. CLA is engaged in a project to examine these procedures and to push for their reform in every jurisdiction in Australia.

In summary, all the initiatives CLA is pushing are what politicians and governments should be doing of their own accord, without the need for constant, external prodding. After all, saving taxpayers money, reducing crime rates, eliminating senseless censorship, and ensuring their citizen’s rights and liberties are protected … that’s almost a definition of good government.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics: see https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/4512.0?OpenDocument ↑

- Andrew Leigh: “The Second Convict Age: Explaining the Return of Mass Imprisonment in Australia”, accessed at: http://andrewleigh.org/pdf/SecondConvictAge.pdf ↑

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2019. The health of Australia’s prisoners 2018. Cat. no. PHE 246. Canberra: AIHW. ↑

- Report on Government Services 2019, accessed at: https://www.pc.gov.au/research/ongoing/report-on-government-services/2019/justice/corrective-services ↑

- Snowball, Lucy and Bartels, Lorana (2013), “Community Service Orders and Bonds: a comparison of reoffending” in Contemporary Issues in Crime and Justice No. 171, Sydney: NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research. ↑

- https://www.alrc.gov.au/publication/pathways-to-justice-inquiry-into-the-incarceration-rate-of-aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-peoples-alrc-report-133/4-justice-reinvestment/what-is-justice-reinvestment/ ↑

- Report on Government Services 2019, accessed at: https://www.pc.gov.au/research/ongoing/report-on-government-services/2019/justice/corrective-services ↑

- The cost of detaining juveniles is about double that of adult prisoners. ↑

- Jarrod Ball: “Australia pays the price for increasing rates of imprisonment”, accessed at: https://www.ceda.com.au/Digital-hub/Blogs/CEDA-Blog/July-2019/Australia-pays-the-price-for-increasing-rates-of-imprisonment ↑

- “No bail, more jail? Breaking the nexus between community protection and escalating pre-trial detention”, accessed at https://www.parliament.vic.gov.au/component/jdownloads/download/36-research-papers/13893-no-bail-more-jail-breaking-the-nexus-between-community-protection-and-escalating-pre-trial-detention ↑

- https://www.audit.nsw.gov.au/our-work/reports/managing-growth-in-the-nsw-prison-population ↑

- https://www.ics.act.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/1450074/10606-ACT-ICS-Healthy-Prison-Review-Nov-2019_FA-TAGGED.pdf ↑

- https://www.audit.tas.gov.au/wp-content/uploads/Full-Report-Tasmania-Prison-Service-use-of-resources.pdf ↑

- https://www.qpc.qld.gov.au/inquiries/imprisonment/

Tasmanian-based Rajan Venkatarman has had a diverse career spanning foreign and domestic policy, trade negotiations, national security and posting overseas. In 2006, Rajan was appointed a member of the Australian Film and Literature Classification Board. He works as an independent consultant and freelance editor, and volunteers as a tutor for adult literacy and numeracy. Rajan is CLA’s main media spokesperson.

Couldn’t agree more with your article Rajan . My brother is currently in prison for a crime he did not even commit and which is supposed to have taken place some 32 years ago !! But try and prove your innocence in this supposed justice system ( not to mention the corruption of police just to get an arrest!!!)

Prison is soul destroying not just for the prisoner but also for their families . Prisoners are treated like animals . My gratitude goes to all the CLA members who believe it can be different snd who work so tirelessly to change the system . I have become a paying member and will also buy a membership for my brother so he may receive your newsletters in prison .

How do I get involved? As a former prison inmate I know what it’s like on the inside. I want to help bring a change to how the system is. So if someone can put me in the right direction please? Prisoners are people too and they need to be treated accordingly.

It is no surprise that the NT stands out. Yes the rate of aboriginal incarceration is massive but at the heart of the problem is the justice system – NT Police and DPP. Sweetheart deals for some and crushing sentences for others. If you are from another state you can guarantee to have a larger sentence than a local. Awful place.